In the central part of the Mediterranean lies an island of about 25,711 km², whose importance dates back millennia. Its strategic position has given it a fundamental historical role, especially in the maritime routes to the Western Mediterranean, as a stopover for numerous expeditions. Through Sicily passed, among others, the Mycenaeans, Cypriots, Phoenicians, Punics, Greeks, Romans, Byzantines and those who interest us most: the Muslims and Normans. Palermo remained under Muslim rule from its conquest in 831 until well into the 11th century, when the Norman arrived to the capital, Balarm (Qaṣr al-qadīm in Islamic sources), today’s Palermo.

In 831, Palermo became the capital of Sicily’s dar al-Islam. Soon after, the Aghlabid dynasty established itself in the city, in its ancient fortified core of Punic origin, although the period of greatest splendor was reached with the Kalbite dynasty, whose government had been entrusted by the Fatimids of Ifriqiya in the 10th century. The journey ended in 1072, with the irruption in the city of the Normans led by Roger I, although it would not be until 1130 that Roger II would take the title of “king of Sicily”. At that time, according to Ibn Hawqal, Palermo had about 300 mosques, none of which have been preserved.

An agronomic revolution

The area of the plain where the city settled, known in Islamic times as Balarm, became known as Conca d’oro from the 16th century onwards. A name chosen for its cultural and natural wealth. Since ancient times, Palermo’s plain has been a place of cultural synthesis, biodiversity and agronomic innovation. The landscape is framed on one side by the Tyrrhenian Sea and on the other by the mountains. A theatrical scenery of exuberant natural beauty.

In 831, Palermo became the capital of Sicily’s dar al-Islam. Soon after, the Aghlabid dynasty established itself in the city, in its ancient fortified core of Punic origin.

This peculiarity was also evident during the Islamic rule, in fact, in the 9th century, Al-Wâquîdi urged Muslim commanders to conquer “a fertile island of copious springs and stupendous fruit trees” (Amari, 1880-1881). Giuseppe Barbera (2007, 14) argues that the first people to arrive to the island in 830 were not soldiers, but nomadic shepherds of Islamic origin, poor farmers who inhabited the margins of the African deserts or small peasants who had fled the Iberian peninsula attracted by the topography of the Quranic paradise that the island was supposed to constitute. The Muslims of Sicily carried out a true “agricultural revolution” with the introduction of new techniques, new species (bitter orange, lemon, lime…), and improvements in the management of water reserves.

More than a revolution, this was a process of cultural syncretism between local knowledge and that brought by the Muslims. A material and immaterial heritage that had its roots in the classical Greek, Punic and Roman traditions… But the scientific bases that they used can be traced back to the kingdom of Al-Andalus. In Cordoba, Toledo and Seville there were important agronomic schools, created as a result of the translation of Greek-Byzantine, Latin and Mesopotamian geoponic texts. The Caliphate garden, distinguished by its variety and natural richness, is the product of this knowledge and experience. This knowledge, in the form of texts, later reached Sicily.

The best representatives of these Andalusian schools visited Palermo on their way to Mecca, bringing with them various innovations. This does not mean that the island was only a place of reception of novelties, but that, on this basis, its scientists developed and consolidated an experimental role that would give rise to new techniques, species and forms.

The Conca d’Oro, a multicultural landscape

This article aims at emphasizing the multicultural nature of the island and the will to integrate and take on board the previous cultural systems, a trend that is still evident today. It should not be forgotten that Palermo is one of the points of greatest influx of migrants who opt for the maritime route when reaching the coasts of the European Mediterranean. The Normans were not oblivious to these circumstances, and, between the reigns of Roger II and Frederick II, they maintained and developed the multicultural tendency so characteristic of Islamic culture. They were aware of the varied society on which they were going to have to govern. They had to legitimize themselves and, in order to do so, they adopted Islamic customs and habits, but also those of the Byzantines, who had previously and contemporaneously dominated the Muslims on the island.

The best representatives of these Andalusian schools visited Palermo on their way to Mecca, bringing with them various innovations.

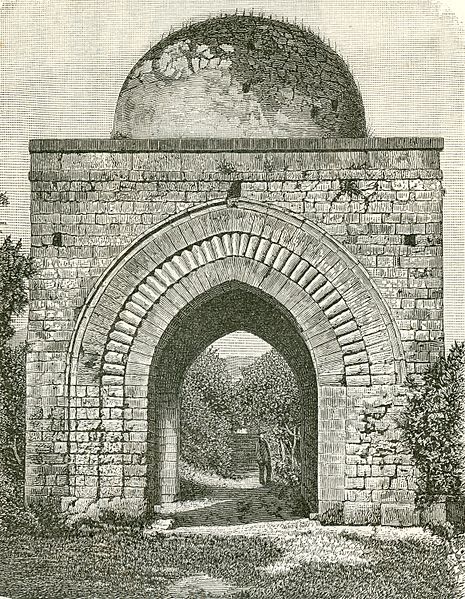

During the Norman rule, in the so-called Conca d’oro, we find a landscape of prolific vegetation, common to the one found in the fertile plains of Granada or the orchards of Murcia and Valencia, and which is defined by ecological efficiency. In other words, there is a clear desire to maintain the Islamic heritage. In fact, as Giuseppe Barberá (2007, 23) describes in his article Parchi, frutteti, giardini e orti nella Conca d’oro di Palermo araba in normanna, “it is quite probable that in a territory long inhabited and exploited like the Palermitan plain, the best sites, those close to water sources, on which the Norman palaces would later be located, were ancient Islamic settlements”. Reinforcing this theory, the Castle of the Favara has been linked to the palace Qasr/ a far, attributed to one of the kalbi emirs bearing the name a far, later occupied by Roger I (1071).

The gardens of the aristocracy coexist in the same territory, together with the cultivated fields and other wooded areas. Despite this typological division, we find a functional continuity between the spaces. The aristocratic gardens were not an exclusive place for recreation, but also functioned as a space for agricultural production, control and distribution of water, as well as for the enjoyment of hunting activities. These gardens were characterized by the cultivation of flowers and fruit trees, the construction of canals and lakes, and the arrangement of pleasure pavilions.

The Norman monarchy was aware of the image of strength and dominance derived from the control of nature, subjected to human wishes to satisfy the desires of pleasure and luxury.

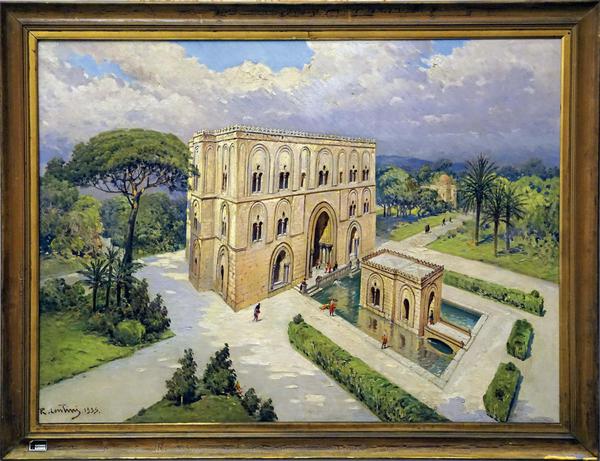

“Palaces of pleasure: Palermo’s suburban gardens and park

The aristocratic garden did not appear isolated, but linked to a suburban architectural structure called, according to Lina Bellanca (2015: 5), “Palaces of pleasure”, whose configuration is determined by the Islamic garden. A clear Fatimid influence can be observed in the architectural forms chosen, but also in the design of the park and gardens, which has its roots in the agdal (a term of Amazigh origin that refers to a private suburban green space, enclosed and equipped with a pool; a model that dates back to the Persians) or buhayra, “small sea”, referring to the characteristic spaciousness of the pools that were used to irrigate the orchard-gardens. In fact, Roger II, William I and William II used Islamic gardeners and architects for their construction.

The Norman monarchy was aware of the image of strength and dominance derived from the control of nature, subjected to human wishes to satisfy the desires of pleasure and luxury. To this end, the monarchs Roger II and William I and II built the “Palaces of pleasures”, according to the research of Lina Bellanca (2015, 5), whose closest parallels are found in Spain. Both have that common Islamic past.

The model followed by these gardens follows this scheme: they are usually located in spaces outside the city, in a panoramic position, endowed with a fence and a formal center. The interior geometric design is distributed by means of water channels lined with flowers, at whose intersections fountains or pools are placed, some of which are so large that they are called “lakes”. In the center of these pools, the existence of small islands has been documented. These large water surfaces acted as mirrors reflecting the large buildings that linked them to the open spaces.

In the case of the Maredolce Castle, also known as the Favara, the Fatimid imprint is more than evident in the forms and construction techniques. While in the garden we find a quadripartite scheme that transports us directly to the Persian agdal or chahar bagh. The Favara still maintains the appearance of this type of garden. In front of the palace, the large water basin (known as the “small sea”), where a small islet used for citrus cultivation and part of the irrigation system that follows the Islamic tradition, is still preserved today.

In a miniature of 1198 from the Liber ad honorem of Pietro da Eboli, we find a high tower, surrounded with palms, vines, fruit trees, birds and wild animals. In the miniature, the place is named Viridarium Genoard, whose etymology refers in Arabic to jannat al-ar (gannat al-ard), “paradise of the earth”. Later, in the 13th century, in the historical sources and in the work of Bocaccio, it would be called the “Cuba” (1189), referring to the quadrangular pavilion that stood in the middle of the garden pool where live fish swam. Apart from the cultivation of fruit trees (peach trees), shrubs such as laurel, wild animals were raised within its walls.

If we look at all these suburban palaces together, with their respective gardens, such as the Zisa, or the Torre Alfaina (Cuba soprana), we realize that they are the surviving remains of a large park. They were not isolated palaces but, despite their private aspect, they created a continuity thanks to the great mass of vegetation that made up the landscape.

The configuration of the Palermo landscape is the result of such a cultural syncretism that historiographical practice has had no choice but to refer, on numerous occasions, to the Norman culture in Sicily as Arab-Norman.

Conclusion

The configuration of the Palermo landscape is the result of such a cultural syncretism that historiographical practice has had no choice but to refer, on numerous occasions, to the Norman culture in Sicily as Arab-Norman. It is impossible to understand the urban landscape of the city of Palermo between the 11th and 13th centuries without paying attention to the material and immaterial heritage inherited from the Muslim populations, who arrived in the city from the 9th century onwards.

When they landed on the island, the Normans were impressed by the lush gardens with their fruits, flowers, trees and plants… To impose themselves in the city, they needed to subdue the existing culture in order to legitimize their power as the successive dynasty. The most efficient means they found to achieve this goal was to appropriate the preceding culture, its knowledge and modes of representation. Not only did they know how to appreciate Islamic culture, but they ended up making it their own, inaugurating an art in which the Islamic garden played a fundamental role in the representation of Norman domination.

Aurora Ferrini – FUNCI

Bibliography:

Amari, M. Biblioteca, arabo-sicula (Torino-Roma: Loescher, 1880-1881).

Bellanca, Lina. Monumenti normanni: sollazzi e giardini (Palermo: Regione Siciliana Assessorato dei Beni culturali e dell’Identità siciliana, 2015).

Barbera, Giuseppe. “Parchi, frutteti, Giardini e orti nella Conca d’oro di Palermo araba e normanna,” Italus Hortus, 14 (4) (2007).

Nef, Annliese. A companion to medieval Palermo. The History of a Mediterranean City from 600 to 1500 (Brill, 2013).

Santoro, Francesco. “I giardini di delizie arabo-normanni nella Conca d’Oro a Palermo,” Bioarchitettura, 56 (2009).

This post is available in: English Español