Alfonso Casani – FUNCI

Environmental degradation is leading more and more institutions and countries to proclaim a climate emergency, including the European Union and Spain. Despite the global nature of climate change, its effects have been specially intense in the Mediterranean region, where the increase in global warming is greater than in the rest of the planet. This article analyses the impact that climate change will have on the countries of the north of Africa and the Middle East (the so-called MENA region) in the coming decades, not only from an environmental perspective, but also from a political and economic one, which highlights the magnitude of the changes and transformations that will take place in the years to come.

The article is based on the considerations contained in the report Mediterranean trends 2030/2050. A prospective approach to the Southern neighbourhood, published by the Spanish think tank Fundación Alternativas in June 2020[1] and drafted by Itxaso Domínguez (coordinator of the Middle East and North Africa Panel at Fundación Alternativas) and Alfonso Casani (researcher at the Islamic Culture Foundation and professor at the University Complutense of Madrid). By identifying different megatrends (long-term dynamics) and medium-term trends, the report offers a series of reflections on the future of the Mediterranean region and the different political, economic, social, technological and environmental challenges it will face in the coming decades.

Among the different megatrends identified, the climate emergency and resource scarcity stand out for their importance. This climate change, identified as a megatrend, is at the pinnacle of the dynamics that will affect the future of the region, due to its global and transnational nature, but also to the particular intensity with which its effects are being felt in the Mediterranean. The urgency of the measures to be adopted against climate change led the European Union to declare a climate emergency in November 2019 and the Spanish government in January 2020, in a clear position in favor of adopting a global and immediate strategy towards a sustainable development that respects the environment.

Expressions of climate change

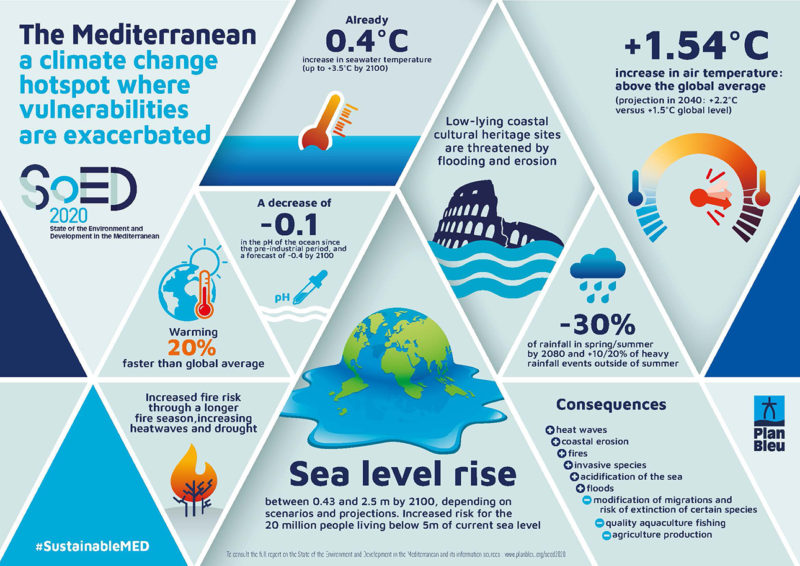

The future forecast of the impact of climate change in the Mediterranean region offers a frightening scenario. The UN has already warned that the effects of climate change are particularly noticeable in the Mediterranean basin, where global warming is occurring 20% faster than the global average. Similarly, the report published by the Fundación Alternativas warns that the temperature has already risen by 1.5ºC above pre-industrial levels, and, if this continues, it will continue to rise to 7ºC by the end of the century.

This increase in temperature will, of course, have major consequences for the environment. Water temperatures have already risen by 0.4°C, and will reach a further 3.5°C by the end of this century. At the same time, it is estimated that water resources will decrease by 20% by 2030 and sea levels will rise to 36 cm by 2050 (the worst UN forecasts even mention a rise of 2.5 metres by 2100). As the infographic below shows, sea level rise could affect as many as 20 million people living in low-lying coastal areas.

Increased desertification, a decrease in crops and arable land, a more intense rainfall (scarce in the hot months and abundant in the winter months), an increase in the intensity and number of heat waves and fires, and coastal erosion are some of the other consequences that will result from the intensification of climate change.

The speed of these phenomena and the difficulties for plant and animal species to adapt to these changes will have major repercussions on ecosystems, leading, notably, to a reduction in biodiversity and agricultural production, as well as an increase in food insecurity. The transformation of climatic conditions is already being felt, leading to an increase in the number of migratory flows among animal species, the gradual movement of plant species to higher altitudes, and even changes in the physiology and morphology of some animal species[2].

The speed of these phenomena and the difficulties for plant and animal species to adapt to these transformations will have major repercussions on ecosystems, leading notably to a reduction in biodiversity and agricultural production, as well as an increase in food insecurity.

Politico-social impact of climate change

The increase in water stress and food insecurity resulting from climate change will, of course, have major repercussions in the Mediterranean countries and will be reflected in the political, social and economic organization of these countries and their capacity to ensure the human security of their populations.

The water and food pressures and the consequent increase in resource scarcity will lead to increased tensions and conflicts, both between and within states, in the coming decades[3]. Internationally, the growing impact of climate change will lead to increased intra-regional tensions as resource scarcity, often shared between countries, becomes apparent. Current tensions between Egypt and Ethiopia over Ethiopia’s construction of a dam on the Blue Nile and the consequences this could have for Egypt’s water supply, or the historical tensions in Jordan and Israel over the use of the Jordan River are a good example of such tensions[4].

Water and food pressures and the consequent increase in resource scarcity to which they will lead will lead to increased tensions and conflicts, both between and within states, in the coming decades.

From a national perspective, water stress and food insecurity will contribute to the intensification of phenomena in full swing, such as demographic growth, urbanization processes and the pressure exerted by the rural exodus on cities, or the degradation of arable land[5]. Food insecurity will also have considerable consequences on the productive capacity of these countries, leading to a decrease in agricultural production and an increase in food prices[6]. All this creates a scenario open to social mobilizations and political tensions, which will intensify the protests that have been taking place in the peripheral regions of the southern Mediterranean countries since 2011, and which reflect the tensions caused by the unequal distribution of and access to natural resources[7].

Increasing intra-state tensions will also be affected by rising sea levels and the future flooding of coastal cities. Basra in Iraq and Alexandria in Egypt are among the main cities threatened by rising sea levels, although their impact could also be felt by other cities in the Nile Delta, Tunisia and Qatar[8]. In addition to the possible human casualties, the eviction of these urban centers (some of which have more than 5 million inhabitants, such as Alexandria) will lead to a strong migratory pressure towards other areas of the country or towards neighboring countries, intensifying the vulnerability of large sectors of the population, and increasing the precariousness of the neighboring cities to which the displaced would be directed. This environmental impact will have a clear class bias[9], affecting the most vulnerable population to a greater extent and widening the already significant economic gap existing within the southern Mediterranean countries.

A global threat requires global solutions

The emergence of the current environmental situation and the profound changes it will lead to require global measures to be taken by all countries. While more and more measures are being taken at the local level to combat climate change and environmental degradation, the transnational nature of this threat also requires state, regional and global solutions.

For this reason, we must emphasize the need for greater regional environmental cooperation to address resource scarcity from a macro-state perspective and to alleviate some of the stress points highlighted throughout the article. The urgency of the measures to be taken may in fact be an opportunity to strengthen diplomatic relations and levels of cooperation in a region characterized by weak South-South relations[10].

The environmental threat is also an opportunity to intensify a process that already seems inevitable: the decarbonization of the Mediterranean basin. The European Union announced its decarbonization plan at the end of 2019, embodied in the so-called European Green Pact. This agreement outlines the short-term objectives to be achieved for the continent. Its main points include the cross-cutting objective of limiting global warming to 1.5ºC; the reduction of net greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030, compared to 1990 levels; and emissions neutrality by 2050. Among its main measures it proposes a raft of emission cuts in transport and industry, energy transformation towards clean energy and increased investment in the fight against climate change, currently also financed through the post-Covid NexGenerationEU recovery plan funds.

More moderately, on the southern shores of the Mediterranean, Morocco aims to obtain 50% of its total energy production from renewables by 2030, while countries such as Algeria, Tunisia and Jordan aim to increase their renewable energy production capacity to 30% by that date. The development of decarbonization processes in the countries of North Africa and the Middle East will, however, be uneven, and will be linked to the political stability of each country and, above all, to their dependence on oil. Thus, countries heavily dependent on oil exports and with rentier economies (such as Algeria or Libya, whose political instability does not allow them to adopt short-term measures in this area) will be more reluctant to embark on these energy transformation processes.

Despite all this, while many of the proposed measures are remarkable, unilateral action by these individual countries will not be enough, and the planet is crying out for more transnational cooperation.

References

[1] The English translation of the report was published in October 2021.

[2] Muluneh, M.G. Impact of climate change on biodiversity and food security: a global perspective—a review article. Agric & Food Secur 10, 36 (2021). Disponible en: <https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-021-00318-5>

[3] MedECC (2020) Climate and Environmental Change in the Mediterranean Basin – Current Situation and Risks for the Future. First Mediterranean Assessment Report [Cramer, W., Guiot, J., Marini, K. (eds.)] Union for the Mediterranean, Plan Bleu, UNEP/MAP, Marseille, France, 632pp. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.4768833

[4] Domínguez, Itxaso y Casani, Alfonso (2021), “Aproximación prospectiva a la Vecindad Sur de España y la Unión Europea: Objetivo 2030/2050”, Fundación Alternativas, núm. 110/2021. Disponible en: <https://www.fundacionalternativas.org/observatorio-de-politica-exterior-opex/documentos/documentos-de-trabajo/aproximacion-prospectiva-a-la-vecindad-sur-de-espana-y-la-union-europea-objetivo-2030-2050>

[5] Lange, Manfred A. (2020). “Climate Change in the Mediterranean: Environmental Impacts and Extreme Events”, IEMed Mediterranean Yearbook 2020. Disponible en: <https://www.iemed.org/publication/climate-change-in-the-mediterranean-environmental-impacts-and-extreme-events/>

[6] International Food Policiy Research institute (2009). Climate change: Impact on Agriculture and Costs of Adaptation, Washington. DOI: 10.2499/0896295354

[7] Thieux, L. y Hernando de Larramendi, M. (2020). Las relaciones Magreb-África: nuevos desafíos e interdependencias. Fundación Alternativas Informe África 2020 Transformaciones, Movilizaciones y Continuidad.

[8] Khamis, Jumana (2020). “Why Middle East cities should worry about climate change”, Arab News, 05/01/2020. Disponible en: <https://arab.news/cazss>

[9] Godfrey, P. C. (2012). Introduction: Race, Gender & Class and Climate Change. Race, Gender & Class, 19(1/2), 3–11. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43496857

[10] Fundación Alternativas, Ibid.

This post is available in: English Español