Review of ‘The Invisible Monument’, by Sara Kamalvand.

When one thinks about the emergence of civilisations and the elements which make them possible, water always appears as foundational. Throughout history, hydric resources have determined where human settlements developed. However, what happens in desert and hostile regions where aridity is the condition? Historically water scarceness hasn’t constrained the flourishing of prosper and sophisticated communities. From this point two main questions arise. How did ancient societies resource water from barren lands? To what extent did this natural obstacle influence their culture and way of life? Both questions are addressed in the new book published by Iranian-Canadian architect Sara Kamalvand.

Born in Iran, one of the driest countries in the world, Kamalvand was drawn to study qanats, traditional underground water extraction systems invented three thousand years ago in her homeland. In 2012, she created HydroCity, a research platform, based in Canada, aimed at delving into these infrastructures and the way they relate at territorial, city, and garden scales. Before setting up HydroCity, she worked for architecture firms such as Zaha Hadid in London and Kirkor in Toronto. She has been guest professor at the École Spéciale d’Architecture in Paris where she taught in the Living the Anthropocene Master-lab, and led a studio at the National School of Landscape Architecture in Versailles, where students had to rethink the relationship between cities and nature. With HydroCity she organised international workshops and exhibitions to conduct research on the abandoned qanat networks and their potential to respond to contemporary issues of resource depletion and pollution footprint, through the design of new gardens and alternative public spaces. Her work brought her to Madrid where she is currently an architecture fellow at the prestigious Casa de Velazquez, (Académie de France institution). The Spanish capital seemingly shares the same heritage; a network of underground galleries was used to bring groundwater to surface for over a thousand years before it was abandoned in the early 1900’s. Called “los viajes de agua”, the qanats of Madrid are a direct transposition of Persian know how in Spain. During her fellowship she published her first book called the Invisible Monument, a thought-provoking graphic novel that proposes an interwoven reading of Tehran placing the qanats in the centre of the story.

Born in Iran, one of the driest countries in the world, Kamalvand was drawn to study qanats, traditional underground water extraction systems invented three thousand years ago in her homeland. In 2012, she created HydroCity, a research platform, based in Canada, aimed at delving into these infrastructures and the way they relate at territorial, city, and garden scales. Before setting up HydroCity, she worked for architecture firms such as Zaha Hadid in London and Kirkor in Toronto. She has been guest professor at the École Spéciale d’Architecture in Paris where she taught in the Living the Anthropocene Master-lab, and led a studio at the National School of Landscape Architecture in Versailles, where students had to rethink the relationship between cities and nature. With HydroCity she organised international workshops and exhibitions to conduct research on the abandoned qanat networks and their potential to respond to contemporary issues of resource depletion and pollution footprint, through the design of new gardens and alternative public spaces. Her work brought her to Madrid where she is currently an architecture fellow at the prestigious Casa de Velazquez, (Académie de France institution). The Spanish capital seemingly shares the same heritage; a network of underground galleries was used to bring groundwater to surface for over a thousand years before it was abandoned in the early 1900’s. Called “los viajes de agua”, the qanats of Madrid are a direct transposition of Persian know how in Spain. During her fellowship she published her first book called the Invisible Monument, a thought-provoking graphic novel that proposes an interwoven reading of Tehran placing the qanats in the centre of the story.

When one thinks about the emergence of civilisations and the elements which make them possible, water always appears as foundational.

To analyse the city as a complex object, the author resorts to in-depth historic and scientific investigation presented through archives, drawings, and designs. The book is co-published by the Iranian artist-run Bon-Gah and Madrid’s La Troupe editorial team. Jaime Narváez of Madrid’s La-Troupe team did the powerful graphic design. The visual narrative is followed by a short essay forming a coherent and meaningful body of work. The book offers a holistic understanding of how this ancient infrastructure influenced simultaneously cosmology and urban form, all the while offering a blueprint of the contemporary capital.

‘The Invisible Monument’

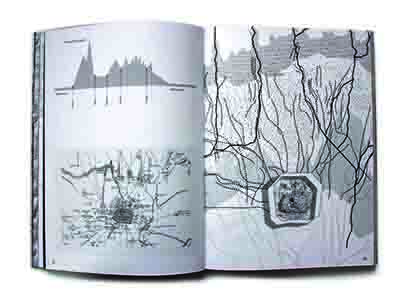

The Invisible Monument unveils the enigma behind the grandeur of the Persian empire in such a harsh environment as the Iranian plateau. One understands how hostile climate and geologic conditions pushed the ancient populations to turn to underground water reserves infiltrated at the foothill of the mountains by melted snow. According to the author, the intricate constructions of the qanat system depended largely on the measurements of slopes combining rigorous scientific methods and traditional knowledge of the territory. The accuracy and complexity of these constructions, taking into consideration the technology available three thousand years ago, is still considered staggering by many experts. Nevertheless, as the author points out and broadens, we should not only consider these as technical feats but look at the qanat as a fundamental device having had a profound influence on economic, social and architectural development. This is where the uniqueness of The Invisible Momnument resides. Taken Kamalvand is an architect she is able to not only provide a rich technical description of the qanat, but beyond this she explores it through multiple themes.

The Invisible Monument unveils the enigma behind the grandeur of the Persian empire in such a harsh environment as the Iranian plateau. One understands how hostile climate and geologic conditions pushed the ancient populations to turn to underground water reserves infiltrated at the foothill of the mountains by melted snow. According to the author, the intricate constructions of the qanat system depended largely on the measurements of slopes combining rigorous scientific methods and traditional knowledge of the territory. The accuracy and complexity of these constructions, taking into consideration the technology available three thousand years ago, is still considered staggering by many experts. Nevertheless, as the author points out and broadens, we should not only consider these as technical feats but look at the qanat as a fundamental device having had a profound influence on economic, social and architectural development. This is where the uniqueness of The Invisible Momnument resides. Taken Kamalvand is an architect she is able to not only provide a rich technical description of the qanat, but beyond this she explores it through multiple themes.

The Invisible Monument unveils the enigma behind the grandeur of the Persian empire in such a harsh environment as the Iranian plateau.

Iran’s two main mountain ranges, the Zagros and Alborz are the political and economic backbones along which all main cities, Tehran, Isfahan, Tabriz, Kashan or Shiraz, are positioned. The Invisible Monument crystallises this axiom by revealing how the existence of theses cities at the foothills is due solely to qanat technology. A territorial strategy that would also allow the extension of the Persian empire, and later of the Islamic caliphates in hostile territories known as the “old dry belt”. From there and following the Muslim expansion, the reader will appreciate how the infrastructure surpassed the Middle East frontiers and fostered the development of consistent agricultural economies and flourishing of distant metropolis, such as Madrid, Marrakech and Palermo.

The author also draws a direct relation between the emergence of fundamental philosophical concepts of the Zoroastrians and the search for hidden resources underground. The adverse conditions which were faced by qanat builders called for a specific comprehensive cosmology that would establish an ecological harmony between humans and earth. While the correlation of this conception with the underground network can apparently be blurred, it is materialised in what is known as the Persian Garden. Furthermore, a broad range of knowledge was fostered by the ancient infrastructure’s development; from the measure of slopes, angles or harvest seasons to mathematics, geometry or astrology.

Tehran development

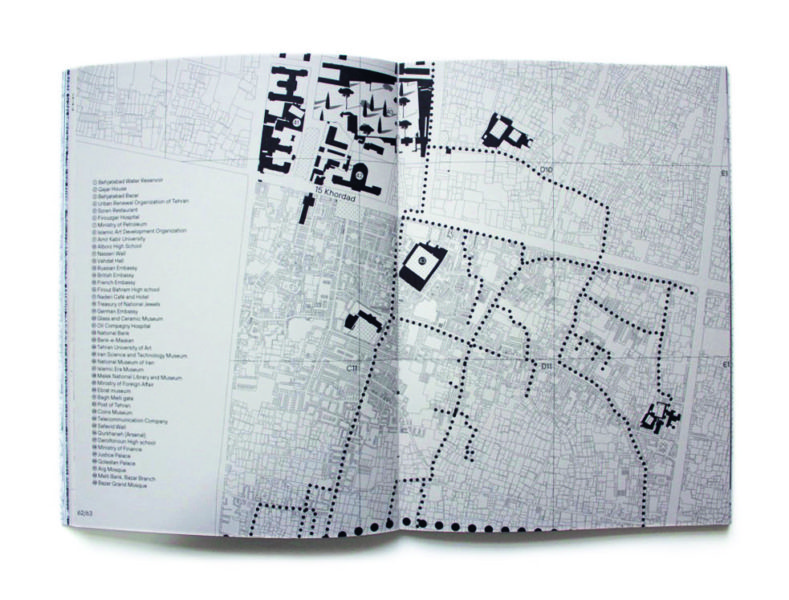

Kamalvand uses Iran’s capital, with a current population of 8 million inhabitants, as her case study. Tehran is decomposed geographically and historically to demonstrate the shaping forces of the infrastructure in thoughts and space. Starting with the etymological relation between the city and the underground canals, The Invisible Monument carries out a reading of Tehran’s development with qanats playing a role in its genesis, morphology and evolution. This development gets interrupted in the 1960’s when radical reforms are imposed by Mohammed Reza Shah. The king commissions Los Angeles architect Victor Gruen to envision the future of the capital. His masterplan based on his life-long research “Cellular Metropolis” places Tehran as an export of the American “Motorcity”. Consequently, a décalage is created between modernisation and local social tendencies pulling the city out of its own roots. It is here, that Kamalvand provides innovative design proposals and schemes to revive the ancient underground network, using the qanat as a reading device but also as a design tool to bring back the ethos based on the garden, further responding to pressing ecological necessities.

The Invisible Monument illustrates how critical water management is to urban design and and its potential when it is done properly.

Finally, we can note that The Invisible Monument illustrates how critical water management is to urban design and and its potential when it is done properly. It is also gratifying to observe how the features, dynamics and complexity of Persian societies detailed in the book sharply contrast with the reductionist Orientalist vision that Western literature tends to portray. Last but not least, we must highlight how the architect who has written the book, Sara Kamalvand, maps the physical and the abstract interweaving human activity, built space and the environment in a surprising and enriching symbiosis.

Toni Sastre – FUNCI

This post is available in: English Español