This is a call for the recognition of the wind and the stars as an Intangible Cultural Heritage. Through Med-O-Med, we want to join this beautiful statement on the importance of tangible and intangible value in nature. In 2007, we already supported the Starlight program for the protection of dark skies and the fight against light pollution, and expressed our commitment to integrate this perspective into our own projects, thus contributing to the preservation of an ecologically sustainable planet.

Astronomy holds an important place in the Sacred Quran. The sky and stars are understood not only as an example of beauty and divine generosity, but also as an important tool for the direction of travellers and a fundamental pillar in the elaboration of the calendar.

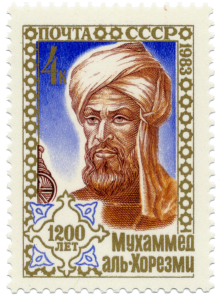

For this reason, Muslims had a crucial importance in the promotion and spreading of this science, both through the translation of classical texts and their introduction to the West during the al-Andalus period, and through their promotion as one of the rational sciences, subject of study for this civilization. Examples of these are the House of Wisdom (9th – 13th century) or, in Madrid (Spain), Maslama al-Mairity (10th century), a prominent astronomer responsible for the translation Ptolomeo’s works and the introduction and adaptation of al-Khwarizmi’s astronomical tables, essential for the understanding of the size of the Earth.

Likewise, Medieval Muslim created several astronomical tools such as the astrolabe and the armillary sphere. They also discovered many stars and constellations, such as Aldebaran, Altair, Betelgueuse, Merak…

But the proverbial Arab art of navigation wasn’t only due to their sense of direction through the stars, but also to their good use of the wind. Thus, the Mediterranean Sea, the Red Sea, the Indian Ocean, etc. saw the proliferation of countless types of Dhows.

Indeed, in the creation of the heavens and earth, and the alternation of the night and the day, and the [great] ships which sail through the sea with that which benefits people… Surah al-Baqara, al-Quran al-Kareem, 162

The wind and the stars: UNESCO’s intangible heritage

Alberto Pereiras

Unesco defines intangible heritage as the oral or living dimension of culture, transmitted from generation to generation. That is, traditions, knowledge, rites, expressions… Today, people identify (and institutions protect) only the intangible value of culture. But what about nature? We live in a time of flags and tribal ties, but if heritage is every natural and cultural good worth valuing and protecting, why to consider only intangible values within the cultural heritage? Why not to protect the wind, the sun’s rays, the flower’s scent, or the wind?

If nature doesn’t inspire us more than material values, such as physical or biological formations (landscapes and species), aren’t we reducing nature to a simple decoration or picturesque furniture? Aren’t we drying it precisely by not taking into account the experience that ties us and integrates us within it? What are the feelings that nature arouses in every living being: the smell of wet soil, the sound of the sea, the cold, and the heat? All those things are the biosphere’s language. A language that, if not listened to, seems silent and prevent us from interacting with it.

If nature doesn’t inspire us more than material values, such as physical or biological formations (landscapes and species), aren’t we reducing nature to a simple decoration or picturesque furniture? Aren’t we drying it precisely by not taking into account the experience that ties us and integrates us within it? What are the feelings that nature arouses in every living being: the smell of wet soil, the sound of the sea, the cold, and the heat? All those things are the biosphere’s language. A language that, if not listened to, seems silent and prevent us from interacting with it.

In the same way that we appreciate material heritage, such as a cathedral, for the immaterial heritage that helps us understand it (such as language or history), society will not really understand natural heritage until we are aware of the language that links us to it: its natural immaterial heritage.

We have grown so far apart from nature that we reduce it to landscapes, forgetting that it is not out there, but inside of everyone of us. And if we don’t feel it inside us, then, we won’t understand that so-called nature until we tune our dial to its frequency. As if we were living in a stagnant dimension. Because most of nature is intangible, an interrelation underlying every landscape we see, a natural melody that has its own weather, soil and biodiversity. For example, Canarias has the sea of clouds, Catalonia has the Tramontane, to which Dalí fell in love to and for which he wanted to build a windpipe organ. More than 2,000 years ago Herodoto narrated the death of several armies in the hands of Simoom or desert poison wind. A nation even declared war to it. And in Switzerland, the Foehn, or witch wind, born in the Alps, is associated to many different types of disorders. A whole wide range of winds blowing since Ancient times and painting landscapes and cultures.

Nature as an immaterial heritage

One might consider absurd to give a heritage status to something like this, as it cannot be protected. But we need to understand protection as “placing value on something”, and we have to take into account that, many times, more absurd traditions have been protected. In addition to this, science did already recognize it in the La Palma Declaration (2007), when it recognized an “inalienable right of human beings”. It is a poetic right, and, above all, a fact that acknowledges reality’s intangible value, as well as how we need or are linked (weather poetically or chemically) to the biosphere. Since then, the Starlight certification for astro-tourisic destinations with no light pollution has risen up the value of many long-forgotten rural areas. All this phenomena constitute the intangible links that keep us together. As they are intangible, they are disregarded by our materialist civilization. Despite of this, they are the equivalent to our artistic heritage, our songs or traditions, but with considerably more valuable, as we depend on them to live (even if we sometimes forget it). To acknowledge this wakes us up from the digital and anthropocentric bubble in which we live and opens us towards the Cosmos reality to which we belong.

One might consider absurd to give a heritage status to something like this, as it cannot be protected. But we need to understand protection as “placing value on something”, and we have to take into account that, many times, more absurd traditions have been protected. In addition to this, science did already recognize it in the La Palma Declaration (2007), when it recognized an “inalienable right of human beings”.

Thus, while society and its institutions value human culture from a double perspective (material and immaterial), nature is valued only from a material point of view, reducing it to a mere museum. Nature is not a decorative or aesthetic good, but a sea of stimulus, a language that entails a superhuman reality that spreads to the stars. In a context of environmental crisis and lack of contact with nature, and according to the model of sustainable progress adopted by the UN, we have to demand for this reality to be included in the immaterial heritage, way before many other symbolic or ethnocentric manifestations. How? By stressing that this is a part of culture and social life, that they existed long before all other cultural goods. In the same way that we appreciate material heritage, such as a cathedral, for the immaterial heritage that helps us understand it (such as language or history), society will not really understand natural heritage until we are aware of the language that links us to it: its natural immaterial heritage.

Source: El Asombrario

This post is available in: English Español