Including the Galiana Palace (Toledo, Spain) into the cooperation platform “Med-O-Med, cultural landscapes of the Mediterranean and the Middle East” gives us the opportunity to learn about the dissemination and conservation work of the palace-garden complex. Primitively, it was the “Almunia Real” or “Almunia Almansura” of the Toledo monarch al-Ma’mûn (11th century). In addition to introducing the new member of the network, this article seeks to approach the historical reality of a place that seems pure fantasy. What lies behind the stories and poetry? What legacy remains of this vanished paradise?

We already anticipate that the real magic of this place resides in its use of knowledge, in the science behind the orchard-garden . The also called “Huerta del Rey” was a true agronomic laboratory. Here, the latest scientific advances of the time were put to the test to create a space that combined pleasure and cultivation, through the creation of orchards and gardens, all framed by a splendid architecture.

Introduction

Last November, we had the pleasure of incorporating the “Palacio de Galiana” to the cooperation platform Med-O-Med. In addition, we were able to meet and talk with its cultural manager, Sofia Palazuelo Barroso. Throughout this meeting we witnessed her passion, love, and dedication to the history of Galiana, its legacy and heritage; a passion inherited from her great-grandmother, Carmen Marañón.

During the Emirate period, the Umayyad dynasty built mansions in the middle of the desert with all kinds of comforts inspired by the ancient ones that came from the East, such as the Palaces of Quasayr Amra, in Jordan.

Sofía Palazuelo is part of the team of Around Art consulting and cultural management, where she oversees the implementation of the project of the Galiana Palace (Toledo), and complements it with cultural activities, events, weddings, and filming. The Palace and former royal almunia of the 11th century was restored for opening and enjoyment of the public.

It is possible to visit, prior reservation, the magnificent architecture of the palace and its gardens, all enlivened with a pond that acts as a mirror, in the image and likeness of the Andalusí garden. But what constituted the so-called “Huerta del Rey”?

On the banks of the Tagus River, this royal orchard of the king, al-Ma’mûn, of the Taifa of Toledo, was built in the 11th century. It was a recreational palace dotted with green and colorful vegetable patches and gardens, where fruit trees, plants and flowers grew forming a beautiful orchard. An inspiring place for historians, chroniclers, storytellers, and poets, who knew how to convey the magic of Galiana.

On the banks of the Tagus River, this royal orchard of the king, al-Ma’mûn, of the Taifa of Toledo, was built in the 11th century. It was a recreational palace dotted with green and colorful vegetable patches and gardens, where fruit trees, plants and flowers grew forming a beautiful orchard. An inspiring place for historians, chroniclers, storytellers, and poets, who knew how to convey the magic of Galiana.

Here took place exciting love stories, such as that of Charlemagne with the Muslim princess Galiana – hence the current name -, the passionate romance of Alfonso VI with the beautiful Jewish Raquel or that of Leonor de Guzman with Alfonso XI, whose love gave place to the dynasty Trastamara. It was precisely this image and the fantasy that this place exudes that inspired Carmen Marañón in 1960 to buy the palace, back then very deteriorated. Together with the architect Fernando Chueca Goitia and the historian Manuel Gómez, the first restoration of the palace accomplished to preserve its originality and historical quality.

Some History. The past of Galiana

During the Emirate period, the Umayyad dynasty built mansions in the middle of the desert with all kinds of comforts inspired by the ancient palaces that came from the East, such as the Palaces of Quasayr Amra (715-718), today in Jordan. These recreational residences, far from urban centers, were organized in halls, pavilions, orchards, and gardens. Munya in Arabic means “rest house surrounded by cultivated fields” (Julián Ramos, 1998, 53). In general, these almunias, were surrounded by groves, vineyards, meadows, and rose gardens, which were protected by a fortified fence. Gradually, after their moment of splendor in the Taifa period, these palaces were moved away from the centers of power, which in Toledo resulted in a series of houses with vegetable gardens and landscaped areas built on the banks of the Tagus River.

Here were lived exciting love stories, such as that of Charlemagne with the Muslim princess Galiana – hence the current name.

In the Vega Alta of the river, a few kilometers from the imperial capital, the “Almunia Almansura”, or “Huerta del Rey”, was built, as a summer residence, by order of the monarch al-Ma’mûn ibn Di-l-Num between the years 1043 and 1075.

Soon, it was shaken by the fierce attacks perpetrated by the Almohad and Almoravid forces, carried out around the nineties of the same century, which continued until the end of the twelfth century. After the famous battle of Navas de Tolosa, in 1212, the Anales Toledanos tell us that the complex was razed to the ground, but, despite such tragic news, it seems that it preserved much of the structure.

During the 13th-14th centuries, the palace was rebuilt in the controversial “Mudejar style”, but it seems that the intervention was limited to the decoration with plasterwork, arches, and painted plinths and the repair of some of its canvases. During this period the palace passed into the hands of the Convent of Jerónimos de la Sisla and was later bought in 1394 by Beatriz de Silva, who married Alvar Pérez de Guzmán. The Guzmán family owned the estate until the 19th century.

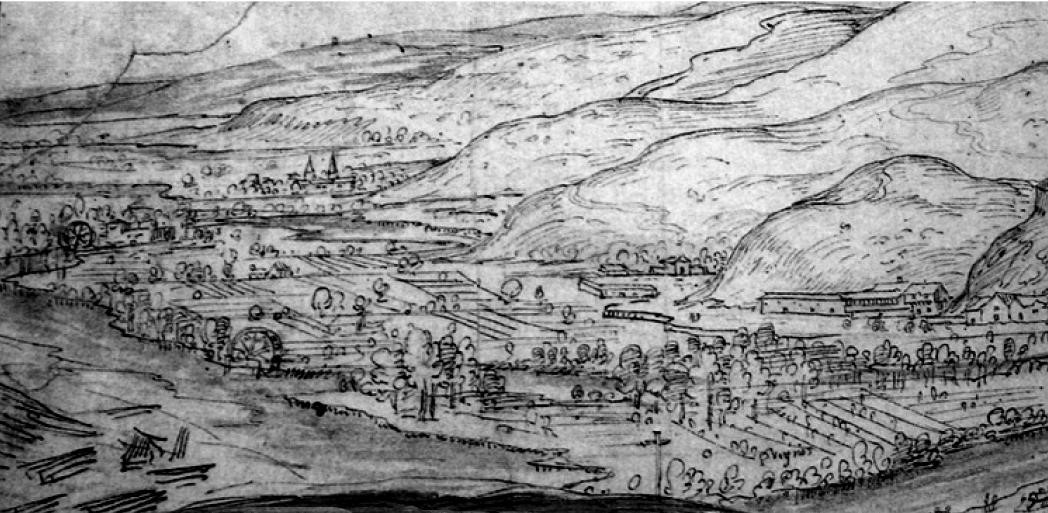

The landscape changed over the centuries, along with the rise and fall of the Tagus, a change to which the “Huerta del Rey” was no stranger. Depending on the time, the crops and the extension of the estate may have varied, but the engravings reveal the continuity of these recreational residences, now many as cigarrales, or stately estates, typical of the humanist character of the 16th century. It appears in the engraving of Wyngaerde, 1563, surrounded by a fence, with a garden watered by two waterwheels and two farmhouses, one of which is still preserved.

From the first 11th century- Islamic palace , we find the original site and the original floor plan , with gardens that recreate those that disappeared at the time.

On the other hand, 19th-century woodcuts show a building already in a ruinous state. Empress Eugenia de Montijo, the last owner of the palace belonging to the Guzmán family, died before she was able to restore the building and bring it out of the state of abandonment in which it was found.

The Galiana Palace was first declared a Historic-Artistic Monument in 1931, and then it was registered as an Asset of Cultural Interest in 1985. From the first 11th century- Islamic palace , we find the original site and the original floor plan , with gardens that recreate those that disappeared at the time.

“La Huerta del Rey”, Science and pleasure

Toledo experienced a truly golden age with the disintegration of the Caliphate into Taifa kingdoms. During the reign of the monarch al-Ma’mûn, the “lover of gardens”, it became the center of cultural and scientific reference, especially for agronomic development. Names such as the cadí Ibn Sâ’id, Azarquiel and Ibn Wâfid stood out in Toledo.

The almunias became “true laboratories of agricultural experimentation” (Jesús Téllez, 50), and their gardens became testing grounds; places where the Koranic paradise took shape.

The so-called “Huerta del Rey”, or “Almunia Real”, was part of this renovating impulse. It was a palatial recreational complex with an important botanical garden and, around it, a large area of horticultural agricultural activity. During the Taifa period, it occupied the fertile land between the Alcántara Bridge and those known as Palacios de Galiana, extending along the Vega Alta del Tajo, on the left bank. A privileged place, enlivened by water and trees.

The planting of the original orchard gardens has been attributed to the Toledo agronomist and scholar, Ibn Wâfid, who used the space for experimentation.

The most outstanding dependency, of which numerous descriptions are preserved, was an apparatus hall called Majlis al Naura (Lounge of the Waterwheel). As its name indicates, there was a waterwheel, located in the garden to which the lounge opened. Itcollected the water from the irrigation ditch that crossed the garden, to irrigate the plantations and to supply water to the pool located in front of the building. This model of a garden with a pool is inspired by the Amazigh agdal, extended with the Almohads,and reminiscent of the African oasis. The Aljafería in Zaragoza, or the Patio de los Arrayanes in the Alhambra of Granada are clear parallels. Inside the pool, there was a gilded bronze kiosk (qubba), the only element of Persian tradition, covered with a glass dome.

Through the use of complicated engineering, they managed to direct and reflect the water “thus achieving a rare atmosphere of fantasy and colorful sensuality” (Julian Ramos, 1998, 59).

Ibn Sa’id al-Magribî’s description says:

In Toledo are the magnificent buildings of the Dhî l-Nûn among which the Alcove of Delights (Qubbat al-Na’im), which al-Ma’mûn had built, stands out. Enveloped by a curtain of water, a sort of vaulted room is created inside, from which he would recline in the coolness of the summer days with some of his best friends, and not even a fly could distract them. That was the case in the Waterwheel Garden.

The planting of the original orchard gardens has been attributed to the Toledo agronomist and scholar, Ibn Wâfid, who used the space for experimentation. Here he acclimatized different plant species and may even have practiced artificial fertilization. Ibn Bassal, on the other hand, devoted himself exclusively to agronomy and botanical studies. He was responsible for the care of the orchard gardens between 1074 and 1075. The knowledge acquired during his intervention in this project helped him, once Toledo was conquered, to create an agronomic school in Seville. Both are credited with the establishment of the first royal apothecary’s shop and the acclimatization of oriental palms in the Iberian Peninsula.

The botanical garden of Ibn Wâfid and Ibn Bassâl was composed of poplar groves, orchards of fruit trees, such as orange and pomegranate trees, and flowerbeds. Here grew exotic, ornamental, or medicinal plants for the preparation of remedies. This explosion of colors was completed with the complex water games resulting from the use of sophisticated hydraulic engineering. In fact, the water clock designed by the astronomer and astrologer Azarquiel (11th century) -which allowed reading the time thanks to the water currents-, could have been situated in the palace. The springs that irrigated the flowerbeds managed to spread so much humidity that they reached the most intimate rooms, making them cool in summer.

Current situation. A unique palace

Currently, the gardens are composed almost exclusively of cypresses, although it is possible to find different flowers such as oleanders, lavender, roses, and pomegranate trees, and climbing plants such as ivy or virgin vine. During spring and summer times, most of them bloom, with lavender lasting until June, although in autumn we can still find pomegranate trees in bloom.

Currently, the gardens are composed almost exclusively of cypresses, although it is possible to find different flowers such as oleanders, lavender, roses, and pomegranate trees, and climbing plants such as ivy or virgin vine. During spring and summer times, most of them bloom, with lavender lasting until June, although in autumn we can still find pomegranate trees in bloom.

The architecture resulting from the interventions stands out for its rectangular shape, the large courtyard divided into corridors that converge in a central fountain, the interior pond that reproduces the possible original location, and the poly-lobed Islamic arches with crenelated perimeter, which recovers the fortified appearance of a medieval era marked by war. The roof is supported by an open gallery, which leads to a beautiful balcony that allows the contemplation of the pond inside the garden. Finally, the main façade still looks out onto the Tajo, whose waters, in constant movement, contrast with the unperturbed Islamic medina of Toledo that looms over the hill.

Conclusions

The Galiana Palace project shares the aims of the Med-O-Med project in the recovery of biodiversity and cultural landscapes in the Mediterranean and the Middle East. It also shares its goals with the recently lanunched Center for the Study of Islamic Toledo, also depending of FUNCI. The objective of this new center is to promote research, dissemination, and enhancement of the tangible and intangible, natural and cultural heritage of the historical region of the Kingdom of Toledo during the Andalusi period and its subsequent legacy. This sums the great value of the adhesion of the Palacio de Galiana , and we hope that it will be fruitful for all the members that make up this network of cooperation and collaboration.

Aurora Ferrini – FUNCI

Information for the visit:

Contact: eventos@palaciodegaliana.es

Schedules:

Winter, November 1st to April 30th:

The Palace conducts tours Friday through Sunday:

– Mornings at 10:00 a.m., 11:00 a.m., 12:00 a.m., and 13:00 a.m.

– Afternoons at 4:00 p.m., 5:00 p.m., and 6:00 p.m.

Summer, May 1st to October 31st:

The Palace conducts passes from Wednesday to Sunday:

– Mornings at 10:00 a.m., 11:00 a.m., 12:00 a.m., and 13:00 a.m.

– Afternoons at 6:00 and 7:00 p.m.

Closed: January 1st and 6th; August 1st to 13rd; December 24th, 25th, 30th, and 31st.

*Visiting hours may change due to events taking place in the castle. In case of closure, alternatives will be offered.

References:

«El Palacio de Galiana: matrimonio perfecto». Jardines Secretos de España, February 2004. Access on January 25th, 2023, https://www.palaciodegaliana.es/assets/images/JardinesSecretos.jpg

Domecq, Ines and Laura Vecino. «Palacio de Galiana: elogio de Toledo y nostalgia del al-Ándalus a orillas del Tajo». Revista Hola, July 2018. Access on January 25th, 2023, ttps://www.palaciodegaliana.es/assets/images/Reportaje_Hola_Palacio_de_Galiana.pdf

López-Quesada, Loreto. «The flourishing grounds at Toledo’s centuries-old Galiana Palace are one of the quiet wonders of Europe». Milleu, December 2015. Access on January 25th, 2023, https://www.palaciodegaliana.es/assets/images/milieumag.pdf

Ramos Ramos, Julián. «Las almunias de la ciudad de Toledo». Tulaytula: Revista de la Asociación de Amigos del Toledo Islámico, Nº 3 (1998): 51-76.

Téllez Rubio, Jesús. «Dos agrónomos toledanos: Ibn Wâfis e Ibn Bassâl, y la Huerta del Rey». Tulaytula: Revista de la Asociación de Amigos del Toledo Islámico, Nº 4 (1998): 49-58.

Vázquez González, Alfonso. «Evolución histórica del paisaje de la Vega Alta de Toledo: Huerta del Rey y La Alberquilla». El Nuevo Miliario, nº 5 (January 2008). Access on January 25th, 2023, https://issuu.com/juaneloturriano/docs/el_nuevo_miliario_5_2008/s/10632877

Vicente, Teresa. «Palacio de Galiana, fortaleza entre cipreses». Vanitas, 4 (2016). Access on January 25th, 2023, https://www.palaciodegaliana.es/assets/images/vanitas.pdf

This post is available in: English Español