Tristan Semiond – FUNCI

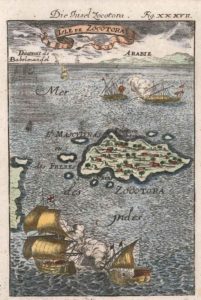

Some 370 kilometers south of Yemen, in the middle of the Arabian Sea and not far from the entrance to the Gulf of Aden – the point of separation between the African continent (Horn of Africa-Somalia) and the Asian continent (Arabian Peninsula-Yemen) – lies a legendary archipelago called Socotra (Arabic and Mehri language: سقطرى).

This archipelago separated from the African continent some 7 million years ago, today rests more than 100 kilometers far from the nearest coast. Its geographical isolation has made it a unique place over time.

It is made up of four islands and several rocky islets. Its main island, which bears the same name, has an area of 3,579 square kilometers, and offers an exceptional variety of landscapes, from white sandy beaches to desert plains or impressive peaks such as the Dixsam plateau, where its highest point is located: Mount Haghier (1,504 m).

A mystical and mysterious island

In the north of Socotra Island, cave paintings can still be seen on the walls of the Hoq cave, which allows us to know that the archipelago was a regular stop for traders from India, Ethiopia, and the Arabian Peninsula, who followed the ancient maritime trade routes of the region.

Despite all the terrifying legends that existed about it, merchants did not hesitate to go to the island, attracted by the exotic resources contained in its lands, especially its incense, whose fame reached Egypt, Greece, and Rome.

For many historians and authors, the island is associated with various mythical tales, influenced by its exotic landscapes. Pliny the Elder (Gaius Plinius Secundus), Roman writer and naturalist, introduced it as the place of origin of the sacred Phoenix. Later renamed the “Island of the Dragons” or the “Island of the Jinn”, its land plays an essential role in many stories in Arab mythology.

In the north of Socotra Island, cave paintings can still be seen on the walls of the Hoq cave, which allows us to know that the archipelago was a regular stop for traders from India, Ethiopia, and the Arabian Peninsula.

Authors and travelers such as Marco Polo and Ibn Batûta also referred to this mysterious place in their works as a place of science, whose inhabitants were “the most learned magicians in the world”.[1]

Initially under the control of the Ptolemaic dynasty, the island was later colonized by Portugal and the United Kingdom, and finally became part of Yemen in 1967.

A unique place with an outstanding biodiversity

The archipelago of Socotra, which some call “the Galapagos of the Indian Ocean”, is now known for its remarkable biodiversity. It was declared a Biosphere Reserve in 2003 and five years later was also recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It is also one of the 200 priority areas defined by WWF (World Wildlife Fund).

Due to its completely secluded geographical position, the island developed its own ecosystem and, according to the latest studies, of the 825 plant species that have been recorded on Socotra, 307 are endemic, representing 37% of the plants. Moreover, some of these types of plants have remained unchanged for 20 million years.[2]

Many of these plant species are very particular and intriguing, such as Dendrosicyos socotrana, the only species in the Cucurbitaceae family that grows like a tree.

In addition, 90% of the reptiles and 95% of the land snails that live there cannot be found anywhere else in the world. The archipelago is also home to important populations of land and sea birds. Of the 192 varieties of birds, 44 breed on the islands and 85 are regular migrants[3].

Within this incredible ecosystem, one plant species stands out for both its importance and its uniqueness, which have made it famous: the Dracaena cinnabari, also called the “dragon tree”.

Within this incredible ecosystem, one plant species stands out for both its importance and its uniqueness, which have made it famous: the Dracaena cinnabari, also called the “dragon tree”.

Dracaena cinnabari, one of the world’s unique trees

Dracaena cinnabari, or dragon tree, is a species that can reach up to 12 meters in height. It is easily recognized by its evergreen foliage that grows in a distinctive way. Its leaves appear only on the tips of its youngest branches and all point upwards. As a result, it looks like this impressive tree wears a green crown resting on its branches.

Its appearance is not a coincidence, quite the contrary, as the species is perfectly adapted to its natural environment and the very arid climatic conditions in which it grows. Everything in nature has its use, and in this case its green crown serves to capture rain, as well as ambient humidity, in order to redirect it to its branches and trunk. In this way, it also reduces evaporation because its formidable leaves provide the necessary shade for this task.

In Socotra, rainfall is scarce and concentrated from October to December, while periods of drought intensify year after year.

In Socotra, rainfall is scarce and concentrated from October to December, while periods of drought intensify year after year. In this context, the dragon tree is essential for the survival of the fauna and flora of the archipelago. It is also a refuge for the nests of bird species endemic to the island, such as the buzzard (Buteo socotraensis), the scops owl (Otus socotranus) and the starling (Onychognathus frater).

A tree recognized since antiquity for its resin

In addition to being very important for the island’s fragile ecosystem, Dracaena cinnabari produces a resin – called dragon’s blood because of its red color – that the inhabitants of the islands (42,842 in 2004) use in traditional medicine, as well as for everyday things such as painting clay and ceramics, dyeing their hair, applying make-up…

The archipelago of Socotra, which some call “the Galapagos of the Indian Ocean”, is now known for its remarkable biodiversity.

The usefulness of this resin was recognized throughout the region, and for this reason it was traded in ancient times by the first inhabitants of the island and the merchants who passed through it. It had a high value because it was harvested only once a year, then transformed into a red powder that, after being heated, offered a highly appreciated paste. It is even said that the red resin of Dracaena cinnabari cured the wounds of Roman gladiators for a long time.

A species threatened for anthropogenic reasons

However, despite its geographical remoteness, the island is not immune to the consequences of climate change and the harmful impact of humans on nature. The last forests of Dracaena cinnabari are becoming scarce and are called Firmihin which means “women” in Socotri. They are all located on the Dixam plateau and have about 28,000 trees, that are between 500 and 1,000 years old.

One of the main threats for the island are cyclones, which are becoming increasingly frequent. One of the most violent, which hit the region in 2015, uprooted some 4,200 specimens – 13% of the forest[4] – while 18,000 people were displaced.[5] Global warming has increased the frequency of cyclones since the early 2000s and some of them hit the archipelago outside the high wind season (usually between May and June).

Although it is a real threat to the dragon trees, cyclones are not the only cause of their gradual disappearance. There is a more common and detrimental threat to the survival of the tree: overgrazing by the numerous goats and sheep that roam freely on the island and graze among the shoots of the plants, thus impeding the regeneration of the dragon trees. This problem is even more serious because this species takes approximately 100 years to reach adulthood and be able to reproduce.

The protection of this natural heritage

In order to preserve the islands, protection initiatives have multiplied in recent years. For instance, a nursery with dozens of Dracaena cinnabari shoots has been created to protect them from goats.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has classified Dracaena cinnabari as a “vulnerable” species and has included it in its Red List of Threatened Species. According to a study based on aerial photography, its population has declined by 78% between 1956 and 2017.

However, despite its geographical remoteness, the island is not immune to the consequences of climate change and the harmful impact of humans on nature.

There are also other potential future threats such as unsustainable tourism, invasive species or the impact of the Civil War. The effects of these threats on Socotra’s biodiversity must be monitored and controlled to avoid another ecological disaster.

If the archipelago continues to be able to stay out of the Yemeni conflict, ecotourism based on well-managed communities could become a boost to the local economy. On the other hand, if urban development is poorly controlled, it could prove disastrous for the environment.

Although the archipelago remains a treasure trove of biodiversity, if no action is taken to protect it, emblematic species could disappear in a few decades.[6] This is a major problem for all the inhabitants of the islands, as less vegetation means more soil erosion and landslides.

[Although] “Socotra is the only island in the world where no reptiles, birds or plants have disappeared in the last 100 years, we have to make sure it stays that way.”

Although “Socotra is the only island in the world where no reptiles, birds or plants have disappeared in the last 100 years, we have to make sure it stays that way,” explains Belgian biologist Kay Van Damme.

Therefore, a sustainable development strategy seems essential to ensure the necessary human and financial resources for the population, while allowing the protection of a diverse and important area.

[1] Amel Boulakchour. « Socotra : une île mystérieuse », Patrimoinedorient.org, 02/03/2020.

[2] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mACW_relB4c

[3] UNESCO/ERI : Socotra

[4] MÜLLER, Quentin. « Dans l’océan indien, le dernier donjon de l’arbre Dragon ». Le Temps, 11/06/2021.

[5] MCCARRON, Leon. « Peut-on encore sauver Socotra, l’archipel yéménite du « sang-dragon » ? ». National Geographic.

[6] « Socotra, un paradis naturel en danger ». L’Union, 10/06/2021.

This post is available in: English Español