Not far away from Faraján urban centre (from the Arabic farhan, happy place), in Malaga province and immersed in a landscape of uncalculated beauty and environmental value, the Al-Andalus originated prodigious hydraulic remains are conserved.

It is known that, as most of the concepts referring to water culture and management, the Spanish word used for designating those special irrigation channels, which was “acequia”, comes from the Arabic word saqiya.

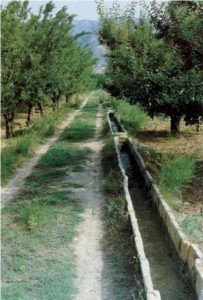

These old-aged traces are irrigation canals (in Spanish “acequia”) aimed at water channelling and distribution, which were dug and built on karstic origin rocks during Andalusi epoch by Muslim individuals from the old Balastar settlement. The infrastructures, were part of a much larger irrigating system attempted at sustainably exploiting the homonymous gully’s plenty flow volume.

It is known that, as most of the concepts referring to water culture and management, the Spanish word used for designating those special irrigation channels, which was “acequia”, comes from the Arabic word saqiya. The Arabs were authentic genius concerning irrigation canals devising, and the designations they used for naming those conduits have transcended until nowadays.

According to what has been collected by Jose Antonio Castillo, Geography Doctorate and President of the Institute for Ronda and Serranía Studies, the Berber Muslim settlers that colonized “Serranía de Ronda” during the VIII Century established their villages at middle hillsides, preferably closer to the merger amid carbonated permeable materials and impermeable siliceous, in order to reach the so called “rigidity line” under which natural springs were born. Those would assure water supply for humans and animals, meanwhile favouring slope’s irrigating structures.

The “water mayor” (in Spanish “alcalde del agua”) figure (the al-qadi al-miyah) was usually occupied by a trust person which used to be a prestigious gardener

The system, sometimes complex, required a predetermined design and needed to be controlled by a specific authority. In this sense, we should outline the “water mayor” (in Spanish “alcalde del agua”) figure (the al-qadi al-miyah). That post was usually occupied by a trust person which used to be a prestigious gardener (known in other regions as the alamín, which comes from the Arabic al-amin al-ma, meaning “the trusted one”), whose role consisted in safeguarding proper water use and respect for watering turns. Furthermore, that leading figure was in charge of irrigating canals maintenance and cleaning, while resolving conflicts surged from the much-appreciated good distribution. The method, emulating customary law, was the humble and local version of the “Water Tribunal” (Tribunal de las Aguas) historical Valencian institution, where a gardener chosen jury dealt with water related disputes and violations.

It is important to highlight how the “water mayor” post is still in force in several cities such as Baza (in Granada).

The importance of irrigation within Islamic Culture.

Since its implementation in the Iberian Peninsula, at the VII Century, the Muslim culture paid special attention to agricultural and irrigation techniques. In its beginnings, Islamic culture recovered, conserved, polished and developed the technologies used by their predecessors in Middle East. The Nabatean, Iranian and Babylonian irrigation techniques, inspired by the Greeks’ scientific ideas and practised by the Romans, were synthesized, developed and diffused by the Muslims. Besides, they inserted novel elements which allowed them to adopt and adapt several technical means and resources to the new settlements orography. These last ones, in general, were aimed at exploratory drilling, catchment, rising, distribution and water use tasks. That supplying, storage and hydric delivery network was the main engine driving the medieval epoch agrarian revolution, by cultivating new Eastern and North African botanical species.

Since its implementation in the Iberian Peninsula, at the VII Century, the Muslim culture paid special attention to agricultural and irrigation techniques. In its beginnings, Islamic culture recovered, conserved, polished and developed the technologies used by their predecessors in Middle East. The Nabatean, Iranian and Babylonian irrigation techniques, inspired by the Greeks’ scientific ideas and practised by the Romans, were synthesized, developed and diffused by the Muslims. Besides, they inserted novel elements which allowed them to adopt and adapt several technical means and resources to the new settlements orography. These last ones, in general, were aimed at exploratory drilling, catchment, rising, distribution and water use tasks. That supplying, storage and hydric delivery network was the main engine driving the medieval epoch agrarian revolution, by cultivating new Eastern and North African botanical species.

The importance of the hydraulic systems brought by the Muslims to the Iberian Peninsula, is evidenced by the water-related Arabisms that we still conserving nowadays in Spanish language. Among these words, we will sketch out not just irrigation canals (“acequia”), but also the diversion dam (in Spanish “azud”, comming from as-sudd), the garden ponds (in Spanish “alberca”, coming from the Arabic al-birka), the waterwheel (in Spanish “noria de corriente”, from al-naura), the animal traction wheel (“aceña”, from al-saniyya), the underground water canals (al-qanat), the coastal lagoon ( “albuferas”, from al-buhayra), the cistern (“aljibes”, from al-y’ibab), and much more.

The travertine Balastar agro system.

Going back to Faraján, its representative paradigm would be the Balastar travertine agro system. This last one displays double terraces placed between level curves alternated with some waterwheels, while being embroidered by two permanent outpourings sound and freshness or by the waterfall which plunges on the surpluses. The subtle, painstaking and laborious configuration of this irrigated space, compartmentalised in smallholdings, perfectly evidences the collective work done by the community due to seeking rational land and water use. The turns were established according to the gardeners’ levels, prioritising the superior terraces in front of the inferior ones, which would get the excesses.

This supplying, storage and hydric delivery network was the main engine driving the medieval epoch agrarian revolution, by cultivating new Eastern and North African botanical species.

It is known that, as most of the concepts referring to water culture and management, the Spanish word used for designating those special irrigation channels, which was “acequia”, comes from the Arabic word saqiya.

Nowadays, the Balastar spot still being rich regarding hydric resources, because of the hillside watering systems prevalence, together with small natural springs and garden ponds. Thus, Faranján neighbours still enjoying this refined and productive irrigation structure, with which they brought water to their small and familiar gardens.

The Balastar irrigation system well-deserves an ethnographic monument appointment or a similar recognition. Around it, several arboreal species are grown, such as cherries, pomegranates, plums, walnuts, olives, figs, oranges, peaches, loquats, and further more which undeniably enrich the magnificent landscape diversity. Besides, the ubiquitous water creates a harmonious, ordered and fresh atmosphere, meanwhile south-oriented wide horizons are sprinkled by flourished slopes boosted by gardeners in this particular vegetal paradise.

Eva Iturbe – FUNCI (translation by Toni Sastre Bel – FUNCI)

Fuente: mundoislam.com

This post is available in: English Español