Islamic civilisation has always been known for its love of landscapes, agronomy and science. Al Andalús, at the heart of Europe, was a perfect example of this predilection.

Gardens as a symbol

When we mention the gardens of Al-Andalús, the first image that comes to mind is of a secluded place for quiet and contemplation, full of flowers, fragrant plants, trees, fountains, ponds and water channels, where architecture is reflected on the water surface, and where light transforms the vegetation with the passing of the hours and seasons. But these gardens are often also large, sometimes stepped spaces affording views over the landscape and expressing the concept of a “power garden”.

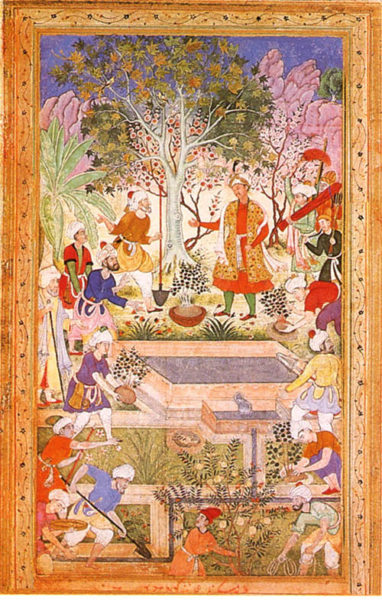

Medieval gardens in the Islamic world, of which hardly any graphic or literary descriptions remain, must have differed from region to region, bearing the imprint of the local tradition but always based on the spiritual concept of gardens as paradise. Oriental gardens came under the legendary Persian influence, with broad avenues, canals, fountains and pavilions in the midst of lush vegetation. The Umayyad dynasty brought the love of gardens with it to the Western Islamic countries, combining the eastern inspiration of wide horizons with the closed, walled garden described in the Koran, which is equally attractive and evocative, and ties in with the hortus conclusus of the Semitic tradition and the peristyle, or Roman patio.

Medieval gardens in the Islamic world, of which hardly any graphic or literary descriptions remain, must have differed from region to region, bearing the imprint of the local tradition but always based on the spiritual concept of gardens as paradise. Oriental gardens came under the legendary Persian influence, with broad avenues, canals, fountains and pavilions in the midst of lush vegetation. The Umayyad dynasty brought the love of gardens with it to the Western Islamic countries, combining the eastern inspiration of wide horizons with the closed, walled garden described in the Koran, which is equally attractive and evocative, and ties in with the hortus conclusus of the Semitic tradition and the peristyle, or Roman patio.

The spiritual garden

Throughout history, the idea of the garden has been linked to the vision of an idyllic, peaceful place, generally in the other world, with rivers and streams flowing through it and an abundance of flowers and trees. The Persian paradise of the Avesta, the Biblical Eden described in Genesis, the Evangelical Paradise or Heaven and the Muslim Paradise all follow this concept of a spiritual garden.

The orchard-garden

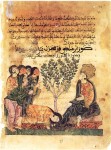

Alongside the walled garden concept was that of the orchard-garden, with open horizons and growing flowers, aromatic plants, fruits and vegetables, with ponds and irrigation channels and pavilions for relaxation. The name given to such periurban gardens was al-munya. Yet another concept were the vast spaces set aside for botanical experimentation and described in the 14th century by Ibn Luyun, an agriculturalist from Almeria in Spain who wrote the famous Kitab al-filaha (“Book of Agriculture”).

Alongside the walled garden concept was that of the orchard-garden, with open horizons and growing flowers, aromatic plants, fruits and vegetables, with ponds and irrigation channels and pavilions for relaxation. The name given to such periurban gardens was al-munya. Yet another concept were the vast spaces set aside for botanical experimentation and described in the 14th century by Ibn Luyun, an agriculturalist from Almeria in Spain who wrote the famous Kitab al-filaha (“Book of Agriculture”).

Documentation exists on the Rusafa garden in Cordoba, one of these acclimatisation gardens, the precursors of the botanic gardens of the European Renaissance. It was built in the 8th century by the Umayyad Emir Abderrahman I, “the Immigrant”. There must also have been a large acclimatisation garden in the palatial city of Madinat al-Zahra, built by Caliph ‘Abderrahman III in the 10th century. In 11th-century Toledo, the al-Munyat al-Mansura (“Victory Garden”) was built alongside the Tagus river, and in Seville, the Almohad Caliph Abu Ya´qub Yusuf had the Buhayra garden built.

During the Al-Andalús period in Spain, many agronomists carried out experiments in these gardens and wrote treatises on agriculture, some of which were subsequently translated into Latin and studied in European universities up to the 17th century. Amongst these experts were Abulcasis (10th–11th century), Ibn Bassal and Ibn Wafid (11th century in Toledo), al-Tignari (11th-12th century in Granada), Abul-Jayr (11th century in Seville), Ibn al-Awwam (12th-13th century, also in Seville) and Ibn Luyun (14th century in Almeria).

“A garden is like a beautiful woman dressed in a tunic of flowers and adorned with a necklace of dewdrops” (Iben ´Ammar de Silves).

This post is available in: English Español