We offer an editorial preview of ‘The Garden Against Time’ (Capitán Swing), by Olivia Laing. The British author narrates how gardens can be places to experience less harmful ways of inhabiting the planet in a context of wars and climate crisis.

‘Even the best tended plots are subject to a relentless barrage of external forces, ranging from weather and insect activity to soil micro-organisms and pollination patterns. A garden is a balancing act that can take the form of collaboration or fierce warfare. This tension between the world as it is and the world humans want is at the heart of the climate crisis, and so the garden can also be a testing ground for experimenting with new and perhaps less damaging ways of inhabiting this relationship,’ argues Olivia Laing in her essay The Garden Against Time, which Capitán Swing has just published in Spain, translated by Lucía Barahona.

Laing spent the pandemic confinement restoring a derelict garden in an 18th century house in Suffolk, a county in the east of England. Out of that experience and his research into earthly paradises comes this book which asks: who can live in paradise and how can we share it while there is still time?

Laing spent the pandemic confinement restoring a derelict garden in an 18th century house in Suffolk, a county in the east of England. Out of that experience and his research into earthly paradises comes this book which asks: who can live in paradise and how can we share it while there is still time?

The British artist shows how the garden is sometimes the scene of rebellious outposts and communal dreams. From the queer utopia conjured up by Derek Jarman on Dungeness Beach to the fertile vision of a common Eden dreamt by William Morris, new ways of life have been attempted among the flowerbeds, experiments that could prove vital in the coming era of climate change.

The following is an excerpt from The Garden Against Time:

‘My father was not a good patient. He was up all the time, he was always banging on the laptop, he never slept, it was impossible to convince him to go back to bed. The builders filled the hole they had made with cement blocks and moved on to other tasks. Ian’s library was progressing, but my garden was in stasis. Walls crumbled and rose again, and with them came showers of mortar. Every morning I went out first thing in the morning to remove it from inside the ferns. Hellebores, daphnes, snowdrops, but everything looked shabby and sleeved by the shoulder. I took refuge in reading, losing myself in Ian’s heavy book which included hand-coloured maps of the bombed areas of London. The site around St Giles was almost all purple. I consulted the legend: damaged beyond repair.

Needless to say, the bombed-out areas were a property developer’s dream. Many were converted into car parks and then into office blocks and luxury housing, literally paving the way for today’s London of glass and steel. But the wild garden that formed in the ruins also presented its own possibilities, for it suggested to a plurality of people the allure of a greener, more fertile metropolis. Many of the City’s ruined churches became public gardens, among them St. John Zachary, the sunflower-filled graveyard in The World My Wilderness, now a pleasant sunken garden with lustrous magnolias and Hydrangea petiolaris, climbing hydrangeas on the walls; St. Dunstan’s in the East, and St. Dunstan’s in the East, and St. John Zachary’s in the East. St. Dunstan in the East, and St. Mary’s Aldermanbury, the Wren-designed church that Hodgkin included in his painting of St. Paul’s Cathedral and which Barbary runs through as she tries to escape from the police. Today it is a shady enclosure on the corner of Love Lane, planted with boxwood knots and yew hedges under two beech trees.

Similarly, in the East End, a number of new parks were established in bombed-out areas or on land reclaimed during the post-war clearance of so-called substandard housing, many of which had been badly damaged in the Blitz, such as Shoreditch Park, Haggerston Park, Mile End Park and Weavers Fields, among others. The social housing estates that replaced these dilapidated homes were often designed with integrated gardens, some of them beautifully planned; part of the post-war settlement that for a time reversed the fashion for enclosures and returned some of Britain’s communal wealth to its poorest citizens. Housing, education, the welfare state: in those years there was a brief conception of the nation as a collective garden, where everyone could share in its fruits.

Perhaps the most ambitious project in this burst of utopian construction is the one that emerged from the ruins around St Giles, the site of the Barbary’s feral wilderness and [John] Milton’s grave. The Barbican is Europe’s largest arts centre and a residential complex housing over four thousand people; a marvel of Brutalist architecture that is also generously endowed with gardens for residents and visitors alike, with concrete balconies gaily decorated with pink and scarlet geraniums. It embodies the concept of public luxury, whose attractions range from cinemas, theatres, an art gallery and library to a tropical greenhouse with fifteen hundred species of rare and endangered plants, as well as ghost carp, grass carp and aquatic turtles. The main attraction is a green-water design lake populated by carp and guarded by herons. It was built on top of the bombed-out Fore Street warehouses and Redcross Street fire station, which went up in flames during the worst night of the Blitz.

Now, really, I only tended the garden at weekends. I would shoot off at dawn and spend all day clearing leaves for compost, discovering snowdrops and the first aconites in their yellow overspikes and grass-green ruffs. I cut the bluebells daily; I was fascinated by the solidity of their whiteness, as dense and shiny as porcelain on their green spouts. The bees liked them too. I found one feasting, and even saw the bright orange pollen overflowing from the basket. I picked that year’s crop of dead nettle, replanting violets as I went, with Who Do You Think You Are Kidding Mr. Hitler on loop in my head, most absurdly. As the light waned, I scraped shepherd’s crooks and old false acacia leaves as I breathed in the damp scent of late January.

February was intermittent, notes scribbled as I went to and from London. Fertilising the boxwood, nurturing the magnolia, planting a Félicité-Perpetué rose on the library wall, my Valentine’s Day present to Ian a day late. Storm Eunice came as I was dividing the bluebells and snapped two branches of the magnolia. Later I heard a crack and, looking out of the window, saw a fallen pine tree in the park behind. I had been thinking about the war for a long time when on 24 February Russia invaded Ukraine and the news was full of bombed cities and displaced people reaching the Polish border on foot with prams and animal carriers. Overnight, even the smallest village in Suffolk had put up Ukrainian flags waving blue and yellow in the breeze.

It is possible for a garden to emerge from a bombed place, but what is certain is that a bomb will destroy a garden.

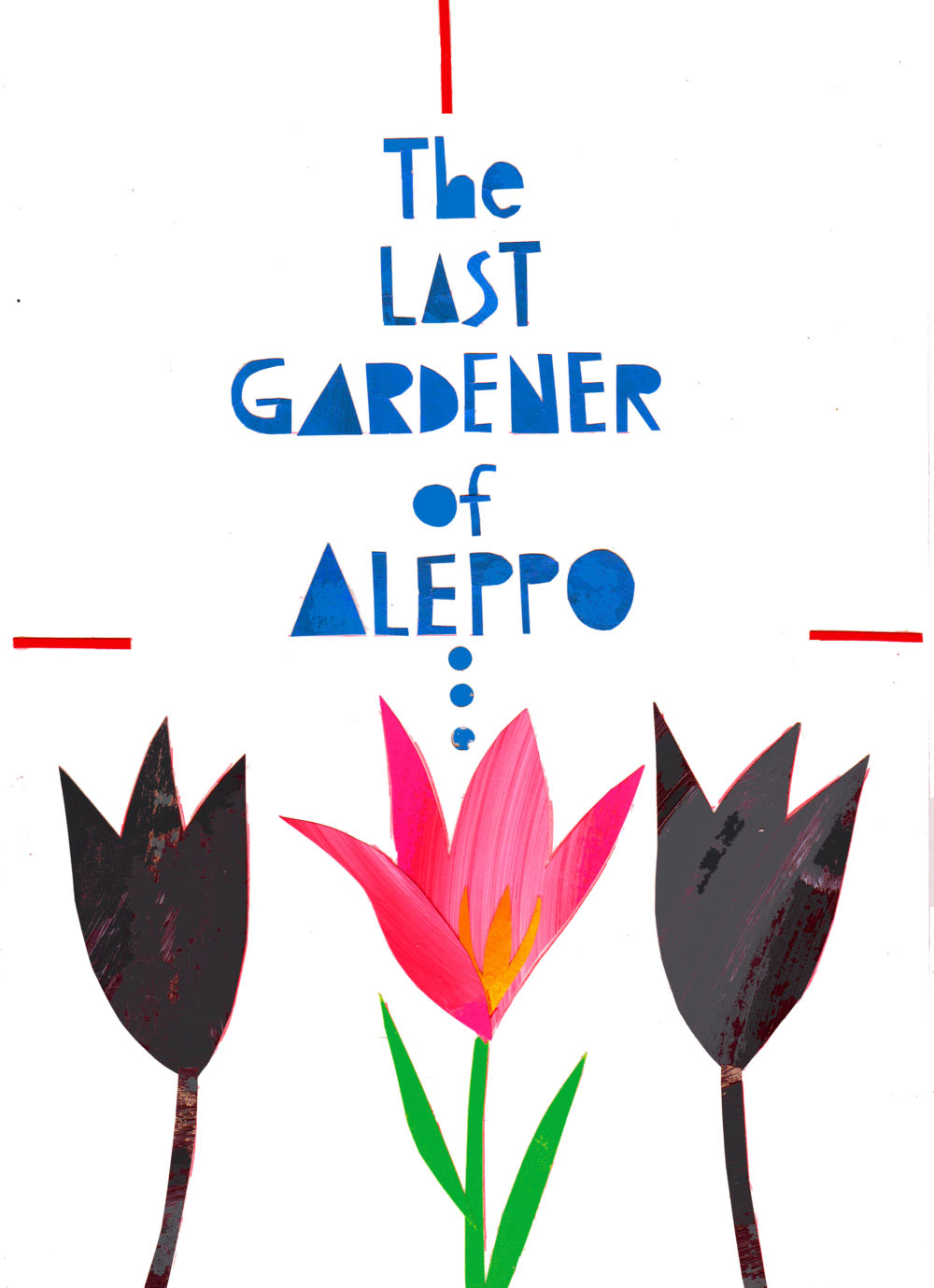

War is the opposite of a garden, the antithesis of a garden, its farthest extreme in terms of nature and human endeavour. It is possible for a garden to emerge from a bombed place, but what is certain is that a bomb will destroy a garden. In the first dreadful week after the invasion, I watched a short film called The Last Gardener of Aleppo several times. Shot by Channel 4 in May 2016, at the height of the Syrian civil war, it told the story of Abu Waad, the head of the last surviving garden centre in rebel-held Aleppo. In those days, the city was being bombed relentlessly, both by the Syrian regime and by the Russians, who were now using the knowledge gained in Aleppo to attack Ukrainian cities.

The film was shot during a lull in hostilities. In the first scene, Abu Waad appeared like Adam naming his plants: hazelnut, loquat and pear trees. He showed the interviewer a tree that had been hit by a barrel bomb. And he assured him that it would survive, he said with absolute certainty: ‘The world belongs to me. The world belongs to ordinary people’. He grew his plants in tins, he knew how to grow the most exquisite roses in the red sand. He explained that his neighbours had bought some of his produce to decorate the roundabouts of Aleppo, a city that has been inhabited longer than any other on the planet. This planting was a statement of defiance, an act of construction amidst the wasteland of the ruined buildings and open craters in which they lived. We saw one of them, strewn with jars of parsley and what was undoubtedly a dragon’s mouth. Then the camera panned to Ibrahaim, Abu Waad’s thirteen-year-old son, hunched back and scared to death, unlike his cheerful father, who was cutting roses for a customer on his way to the local hospital.

The film was shot during a lull in hostilities. In the first scene, Abu Waad appeared like Adam naming his plants: hazelnut, loquat and pear trees. He showed the interviewer a tree that had been hit by a barrel bomb. And he assured him that it would survive, he said with absolute certainty: ‘The world belongs to me. The world belongs to ordinary people’. He grew his plants in tins, he knew how to grow the most exquisite roses in the red sand. He explained that his neighbours had bought some of his produce to decorate the roundabouts of Aleppo, a city that has been inhabited longer than any other on the planet. This planting was a statement of defiance, an act of construction amidst the wasteland of the ruined buildings and open craters in which they lived. We saw one of them, strewn with jars of parsley and what was undoubtedly a dragon’s mouth. Then the camera panned to Ibrahaim, Abu Waad’s thirteen-year-old son, hunched back and scared to death, unlike his cheerful father, who was cutting roses for a customer on his way to the local hospital.

Six months after this sequence was filmed, a bomb fell next to the garden centre and Abu Waad was killed instantly. Ibrahaim was interviewed again, though this time he could barely speak, he was somewhere beyond where words come from. The film returns to Abu Waad in his garden in spring, smoking, drinking tea, pruning a rose bush. Flowers help the world,’ he said, ’and there is no greater beauty than flowers. Those who see flowers enjoy the beauty of the world created by God. The essence of the world is a flower’.

In times of war, perhaps it is enough that a garden simply exists, a sworn statement that there are other ways to live a life, that generosity, kindness and cultivation count too, despite its perpetual vulnerability. A war garden provides some sustenance even when it is not meant for growing cabbages and carrots, for gardening plots and ‘digging for victory’. And sometimes a garden can also be a shelter in the literal sense of the word. Its doors can open, it can go from being private to a shared sanctuary. That spring I found myself thinking often of a garden I had seen in Italy: a lush, aristocratic garden of descending terraces and fountains, box hedges forming flowerbeds and cypress trees, all so green and orderly on a hillside that it almost looked odd in the harsh, whitewashed landscape of the Orcia valley, a region of Tuscany roughly halfway between Florence and Rome. In the 1940s a tin box was buried in this garden containing a diary that recorded – day by day and sometimes hour by hour – the hostilities and terror that convulsed the region during the Second World War; a testament to the many different purposes a garden can serve’.

Cover photo: Sandra Mickiewicz

Source: Climática.

This post is available in: English Español