(Cover photo: David Silverman / Getty Images) The video opens with images of sun-drenched rows of vegetables, a pair of hands carefully selecting greens, a beautiful leafy salad and workers sharing a meal. A young woman, Yara Dowani, is presenting the community-supported agriculture (CSA) farm that provides organic vegetables to about 25 families. While she describes running collective workshops on natural farming and building, the viewer’s eye is drawn to the white modern buildings behind her. They are part of Modi’in Illit, one of the biggest illegal settlements in the occupied West Bank. The farm that Dowani manages, Om Sleiman, is in Bil’in, west of Ramallah, a village known for its weekly protests against Israel’s separation wall, captured in the award-winning documentary “5 Broken Cameras.”

A lopsided struggle has been going on for decades between the dominant global food corporations and international social movements calling for food sovereignty, defined by the international peasant coalition, La Via Campesina, as “the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods and their right to define their food and agriculture systems.”

Today, with the urgent issue of climate change, coupled with two years of a global pandemic, people are looking more closely not only at industrialized agricultural practices as one of the largest contributors to climate change, but also to global food insecurity with the poorest countries seeing sharp increases in food prices.

These are all issues familiar to Palestinians living in the West Bank who endure a brutal occupation, well documented in a February 2022 Amnesty International 280-page report, “Israel’s Apartheid Against Palestinians: Cruel System of Domination and Crime Against Humanity.” A specific study on small-scale agriculture in the Palestinian Territories submitted to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) in 2019 had found that “the Israeli occupation is the most important single driver of food and nutrition insecurity.”

But amid this hardship, people involved in agriculture, a pillar of Palestinian history and culture as well as its economy, have, against all odds, been finding new ways to pursue food sovereignty—in itself a form of resistance and self-determination. (Only the West Bank will be covered here; for information about the situation in Gaza, the U.S.-based nonprofit organization Just World launched a webinar-based project on the subject in November 2020.)

A green and social space in Bil’in

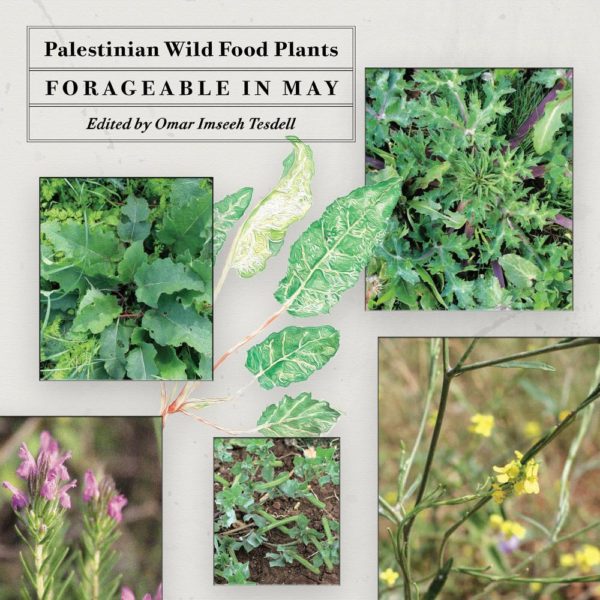

Yara Dowani grew up in Jerusalem but came to farming after taking a permaculture course in the West Bank, which “took me away forever,” she said. After working on farms in Spain, she studied wild perennial plants and contributed to a book about Palestinian edible plants edited by Omar Tesdell, who focuses on landscape and agroecological transformation at Birzeit University in Ramallah. In 2018 she came to Om Sleiman farm, which was founded in 2016 by Mohammad Abu Jayyab and Muhab Alami, who were offered land by Bil’in resident Abu Alaa Mansour. On it, they sought to create a social, ecological and economic space working with farmers and consumers, villagers, and city-dwellers.

Bil’in’s land is dry and rocky. Moreover, it is in Area C, one of the three administrative divisions created in the 1995 Oslo Accords. Area C contains 63 percent of the land in the occupied West Bank and is under full Israeli civil and security control. It’s also where the illegal settlements are located. Water shortage is a severe problem: According to the United Nations, Palestinian per capita access to water in the occupied Palestinian territories is below the internationally recommended level of 100 liters. Israel controls 85 percent of Palestinian water sources and although most of the water originates in the West Bank, Palestinian farmers are denied the right to excavate wells, and permits for any other construction are regularly rejected.

Since you can’t have your own well, says Dowani, farmers will sometimes use the “ba’al” method, “which is an amazing rain-fed technique. You can plant your tomatoes, watermelon or cucumbers in March, when the soil is still humid, and not water them at all.”

But this ancient way of farming — the word comes from the Canaanite god of fertility and destruction who during years of drought was worshiped in the hope of rain — has become more challenging with climate change because of inconsistent seasons and rainfall. The land must be plowed multiple times before it is planted and at a specific moment when the soil is humid from rain but not too damp, says Dowani, but this fits into the adage of “how to turn problems into solutions.”

It’s also a way of reconnecting and working with ancient practices that have been in place for over 3,000 years, as in the village of Battir where its terracing and an irrigation system date from Roman times. The ancient vine terraces of Battir were placed on UNESCO’s World Heritage list in 2014, but they are also on the organization’s World Heritage in Danger list because of Israel’s plans, on hold since a legal case in 2015, to build a segment of the separation wall in the village.

Sari Khoury, founder of the wine label Philokalia, which began producing in 2018, uses nongrafted, native Bethlehem grapevines, applying the ba’al method. Moreover, he draws on the wisdom and knowledge of an older generation, working with a handful of farmers all over 70 years of age. An architect by profession, Khoury came to winemaking via a chance encounter with Paris-based Palestinian artist Nasser Soumi. Soumi was born in the Jenin area in 1948, the fateful year of the Nakba, and his family soon left for Jordan. As a child Soumi had “an inexplicable passion for wine,” he said, and even made his own when he was 14 years old. Soumi’s dream was to become a winemaker on land his godfather owned in the Golan Heights, but that dream was shattered, he said, when Israel seized the Golan Heights in 1967. Soumi studied art and moved to France but continued to research the history of wine, marveling at the Abydos jars in the Louvre Museum that archaeologists discovered had once contained wine from Palestine that was exported to Egypt during the early Bronze Age. When Khoury met Soumi, Soumi not only transmitted his passion for wine to the younger man but also “introduced me to elements of Palestinian history. I started to see how colorful our past was vis-à-vis these gray moments,” said Khoury. He drew up a plan for a vineyard near Bethlehem that would continue to use age-old methods in the distinctive, natural environment of the area. “All the arrows pointed in the same direction, whether practical, technical or political,” said Khoury. Today Philokalia, which means “the love of the beautiful/ the good” in Greek, produces from 5 to 6 thousand bottles of wine a year, with labels designed by Soumi, as well as three grades of arak (an anise-based spirit) and a clear brandy infusion made with tobacco from Isfahan. Khoury searches for forgotten grape varietals, and inspired by old farmers, uses wild plant infusions as a fungicide. “Philokalia is a project of values,” said Khoury, “researching your history, working a certain way with people and using a minimal level of intervention in the cultivation.”

Checkpoints, the army, the closures, the settlers, taxation, bureaucracy and the high cost of production are all hurdles, says Khoury, “but we need to try to be creative no matter the situation we’re living in. We need to work on things that are within our reach and think about what it means to be Palestinian and where are we trying to go.”

Nasser Abufarha grew up in a farming community in the Jenin area and began thinking about what he wanted for Palestine in 2003 during the second intifada, when he returned from the U.S., where he had earned a doctorate in anthropology. While in the U.S., he had also become acquainted with the concept of fair trade, a certification system that sets standards and contributes to sustainable development by including small-scale farmers and producers in decision-making.

“Anthropology allowed me to distance myself from events and analyze them; it helped me reframe activism in my mind. I looked at similar struggles in southeast Asia, Africa or Latin America and at the long-term, humanistic perspective,” said Abufarha.

Economic development under occupation

He decided to concentrate on what he calls the backbone of the Palestinian economy, the olive crops. “Two hundred thousand families have olive trees. One hundred thousand families are dependent on the olive trade to subsist. We are literally cultivating trees that are 5,000 years old and more. The farmers who care for these trees and nurturing and protecting this ecosystem is what is at stake here. What’s left of farming in the West Bank is a beautiful, cultural, world heritage. Israeli occupation and expansion are ruining this ecosystem of vegetation and communities. If this is ruined, it’s gone forever.”

According to the Palestinian Grassroots Anti-Apartheid Wall Campaign, a coalition of Palestinian nongovernmental organizations, in 2020 Israeli soldiers and settlers uprooted or burned more than 8,400 trees, part of an ongoing series of attacks on Palestinian farmlands. Already between 2000 and 2006, the U.N. Conference on Trade and Development had stated that Israel uprooted 1 million trees in Gaza and approximately 600,000 in the West Bank.

The indefatigable Abufarha began, in his words, to preach the concept of fair trade to farmers across Palestine. He developed standards and guidelines for olive oil, formed collectives, held workshops and in 2004 founded the Palestine Fair Trade Association (PFTA), which became the first organization in the world to be fair-trade-certified for olive oil. The PFTA was included as an example in a 2014 International Labor Report entitled “Learning from catalysts of rural transformation” and today brings together 2,500 farmers, including a number of women’s cooperatives.

Abufarha also established his private company in 2004, Canaan Fairtrade, which buys olive oil, almonds and other products from the PFTA and sells them abroad. “In 2005 we had three clients. Then in 2006 Dr Bronners Magic Soaps became a client and bought 60 tons of olive oil for their soaps. After 2006, people realized this wasn’t just an activist project,” smiled Abufarha.

In 2013 he created the Canaan Center for Organic Research and Extension, which supports sustainable agro-ecology in Palestine, raises public awareness, and provides education and training, themes that correspond to what Dowani and the Om Sleiman team want to focus on.

In the little free time she has, Dowani volunteers with a group called Sharaka, part of the slow food movement, which connects Palestinian consumers directly with local producers. In the spring and summer Sharaka organizes markets on a weekly basis. Other grassroots organizations such as Raya Ziada’s Manjala aim to reconnect children and young adults to the land and its agriculture in an attempt to stave off the hegemony of Israeli produce that floods the West Bank. Agronomist and environmentalist Saad Dagher, like other activists worldwide, is encouraging the recovery and use of original local seeds for use in agriculture, while anthropologist Vivien Sansour founded the Palestine Heirloom Seed Library in Battir, where heirloom seeds are saved, reused and planted.

Foraging for wild edible plants is also a time-honored practice in Palestine that’s seeing a renewed interest. As with everything in the region, though, foraging is political.

Berlin-based visual artist Jumana Manna grew up in East Jerusalem, where her parents have always foraged for delicacies such as ‘akkoub (gundelia), za’atar (thyme/hyssop), hindbeh (dandelion), or halayoon (wild asparagus), all widely used in Palestinian cooking.

But picking za’atar, ‘akkoub and miramiyyeh (sage) became a criminal offense punishable by fines and up to three years imprisonment, beginning with za’atar, in 1977, when the Israeli Nature Protection Agency decided it should be a protected species.

Manna’s new film, “Foragers,” to be released in March, looks at the effect of the prohibition of ‘akkoub and za’atar picking on cooking in Palestinian homes. Manna described her film as having different elements that include the relationship Palestinian foragers have to their landscape, their confrontation with a bureaucratic system, a “comedic, absurd aspect” that includes chase scenes with the Israeli nature patrol, surveillance technologies and finally, a series of scripted court hearings based on real cases. For the court hearings, Manna used research done by Rabea Eghbariah, an attorney and scholar currently in the doctoral program at Harvard Law School.

Eghbariah is a ’48 Palestinian, one who lives within the borders of the Israeli state founded in 1948. Born in Haifa, he said that all Palestinians forage for wild edible plants; it’s a practice that “crisscrosses gender and class.”

Eghbariah began to investigate the ban on foraging the three plants, suspecting that it had a far greater significance than simply protecting nature. Rather, as he said in a recent episode on the podcast “Palestine, In Between” at Columbia University: “ … I do believe that za’atar and ‘akkoub at the end of the day represent a wider story about Palestinian dispossession from their land. And in general about the Nakba being a process and not only an event in which Palestinians lost control over the smallest details of their lives.”

While everyone agrees that plants should be protected, Eghbariah, in a paper presented at the 2020 Oxford Symposium on Food & Cookery called “The Struggle for Za’atar and ‘Akkoub: Israeli Nature Protection Laws and the Criminalization of Palestinian Herb-Picking Culture,” writes that for centuries Palestinians have been foraging these herbs with no scientific evidence that the practice endangered their growth.

He goes on to quote Israeli botanist Nativ Dudai: “No one talks about the fact that we, the Jewish [Israelis], destroy much more za’atar than the Arabs pick. Do you know how many great za’atar populations were uprooted by bulldozers? In Har Adar or Elyaqim interchange—locations with beautiful amounts of za’atar, and all of it is now gone. But the Arab? He picks five kilograms and gets a fine.”

In 2019, working with Adalah, a legal center for Arab rights in Israel, Eghbariah demanded that picking the wild herbs be decriminalized, arguing in a letter to Israeli authorities that the ban was not based on reliable facts, did not serve the purpose of the law and disproportionately harmed the Arab population that had been using these herbs for hundreds of years. A year later enforcement measures were softened, allowing people to collect up to five kilograms of edible plants for a trial period of two years.

Palestinian chefs, too, have been playing their part in supporting Palestinian farmers, because as Bethlehem-based Fadi Kattan says, “Without them, chefs and food people don’t exist.” Kattan uses local Palestinian produce and is working on refashioning traditional Palestinian cuisine all the while admitting that “my cuisine will disappear, but my grandmother’s won’t.” His “Fawda” restaurant has been on hold since the pandemic, but in the meantime, he has worked on a podcast called “Sabah Al-Yasmine” and a web series called “Teta’s Kitchen”; both educate and inform about Palestinian cuisine. He’ll also be opening a Palestinian restaurant in London called “Akub,” named after the much-loved and foraged wild plant. He’s not interested, he says, in continuing to argue that hummus is not Israeli. “I want to talk about mansaf and freekeh. I want to celebrate our products.”

Abufarha concurs: “We need to preserve our culture that has sustained us so far. If we preserve our integrity with our land, we preserve our cultural and societal unity and we remain steadfast.”

Both Abufarha and Kattan would like to map Palestinian terroir in cooking and agriculture, registering origin and provenance.

Clearly, the Palestinian community, whether in the occupied West Bank, within the Israeli borders or in the diaspora, is working on preserving and reviving ancestral agricultural practices and sustainable farming as a path to increased food sovereignty.

“People who are committed to this lifestyle and movement aren’t fulfilling an economical or trend-based motive,” says Yara Dowani. “It’s deeper, it’s resistance. … All over the world people want to have a community and live self-sufficiently; this is the romantic part. To actually make it happen you have to be on the land and sacrifice a lot. The farm is your home and you spend 12 hours a day working on it … but it’s social and political, and if I’m here, it’s because there’s nothing more I’d rather do.”

Author: Olivia Snaije

Source: Newlines Magazine

This post is available in: English Español