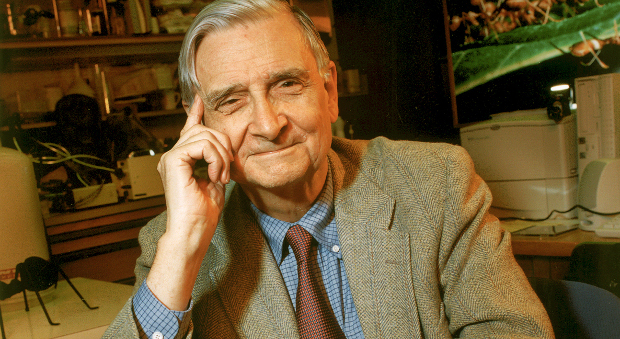

The BBVA Foundation Frontiers of Knowledge Award in the Ecology and Conservation Biology category goes to American naturalist Edward O. Wilson, “one of the most influential thinkers of our time, an exceptional biologist and a world-class natural historian”, in the words of the prize jury. Wilson “coined and popularized the term ‘biodiversity’, which is the label for global conservation issues and efforts across the globe, and has contributed much to making our society aware of its value”.

“one of the most influential thinkers of our time, an exceptional biologist and a world-class natural historian”

The jury points out that Wilson’s seminal contributions started from something as concrete as the study of ants: “His career in science has expanded on his life-long fascination with the biology of ants to permeate all of ecology and conservation biology”.

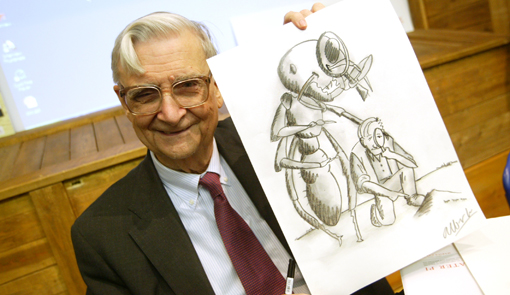

‘Lord of the Ants’

A sobriquet often pinned on Edward O. Wilson (Alabama, 1929), Emeritus Professor at Harvard University (United States), is ‘Lord of the Ants’. His passion for these insects, dating from his earliest childhood, has led him to fundamental contributions not only in biology but also in the social sciences. Hence Wilson – commonly referred to as a naturalist and humanist – is the founder of sociobiology, the discipline inquiring into the biological bases of human conduct, and has won the Pulitzer Prize on two occasions: in 1979 for On Human Nature and in 1991 for The Ants.

As an entomologist, he was the first to describe the social behavior of ants and other social insects. He also succeeded in deciphering the ‘chemical language’ they use to communicate and plan their routes, and in demonstrating the action of pheromones.

This work was also at the root of his island biogeography theory, developed in the mid 1960s with Robert MacArthur and now considered a fundamental tool for the design of conservation strategies. This theory recognizes that simply setting aside a parcel of the right habitat is not enough to ensure that a species will survive, an insight that has led to “improved design of nature reserves to minimize extinctions”, the citation continues.

Regarding his many contributions outside the strictly biological arena, the jury remarks that his writings “have linked human culture to evolutionary ecology”. His books Sociobiology and Consilience “provided a firm basis for the new discipline of evolutionary psychology that is currently revolutionizing fields as disparate as anthropology, linguistics and history”.

The concept of consilience rests on the idea that the sciences, humanities and arts are not isolated branches of knowledge, but together convey, in Wilson’s own words, the message that “the world is orderly and can be explained by a small number of natural laws”.

“His impact has been truly extraordinary in creating and inspiring new areas of ecology and conservation biology, and indeed of science in general and its popularization”, in the jury’s opinion. “There are few biologists working today who have not been influenced in some way by his work and writings.”

“A culminating award”

“This, for me, is a culminating award”, said Wilson on being informed of the jury’s verdict. “It is a very substantial prize in view of the stature of the jury and its world-wide reach. But also because it recognizes the advancement of knowledge in the broadest sense. We are now in an age where the greatest need is for synthesis, the ability to take all the discoveries made in science to create a more unified body of knowledge. That seems to me to be what the BBVA Foundation is recognizing”.

“This, for me, is a culminating award”, said Wilson on being informed of the jury’s verdict. “It is a very substantial prize in view of the stature of the jury and its world-wide reach. But also because it recognizes the advancement of knowledge in the broadest sense. We are now in an age where the greatest need is for synthesis, the ability to take all the discoveries made in science to create a more unified body of knowledge. That seems to me to be what the BBVA Foundation is recognizing”.

At the age of 81, Wilson has lost none of his fascination for ants and observes them wherever he goes: “I will certainly enjoy looking out for them when I come to Madrid for the award ceremony”, he muses. And he stresses how much we humans have to learn from them. “They have the most complex social systems of any creatures in earth, apart from humans. People often ask me how I can connect ants to people, and I point out that the study of ants has had a huge influence on the study of human behavior”.

Wilson sees some cause for optimism in that “the idea of biodiversity is now everywhere”, but calls for more effective action to conserve it. “I have to say that the public and politicians are insufficiently aware of the importance of biodiversity”. He insists, for instance, that “we have only described about 10% of the world’s insects” and that filling these huge gaps in our knowledge of the organisms that share our planet is vital to our own development.

The boy who loved bugs

“Most children go through a phase of being fascinated by bugs; I guess I never outgrew mine,” writes Wilson in Naturalist. And indeed his entomological passion came to him at an early age. At nine, he undertook his first expeditions at the Rock Creek Park in Washington, DC, and at thirteen, in Alabama, he discovered his first colony of fire ants. At the age of eighteen, intent on becoming an entomologist, he began by collecting flies, but the shortage of insect pins caused by World War II convinced him to switch to ants, which could be stored in vials. After taking a biology degree at the University of Alabama, he obtained his doctorate from Harvard, to which he remains associated to this day. Indeed beneath his office in Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology lies the world’s largest ant collection, comprising almost one million specimens of 5,000 varieties.

“Most children go through a phase of being fascinated by bugs; I guess I never outgrew mine,” writes Wilson in Naturalist. And indeed his entomological passion came to him at an early age. At nine, he undertook his first expeditions at the Rock Creek Park in Washington, DC, and at thirteen, in Alabama, he discovered his first colony of fire ants. At the age of eighteen, intent on becoming an entomologist, he began by collecting flies, but the shortage of insect pins caused by World War II convinced him to switch to ants, which could be stored in vials. After taking a biology degree at the University of Alabama, he obtained his doctorate from Harvard, to which he remains associated to this day. Indeed beneath his office in Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology lies the world’s largest ant collection, comprising almost one million specimens of 5,000 varieties.

Besides his Pulitzer winning publications, his best known books are his autobiography Naturalist, and the titles Sociobiology, The Diversity of Life, Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge and The Future of Life.

Edward O. Wilson’s name was put forward for the award by herpetologist James Hanken, Director of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University (United States).

International jury

The jury in this category was chaired by Daniel Pauly, a Professor of Fisheries at the University of British Columbia Fisheries Centre (Canada), with remaining members Paul Brakefield, Professor of Zoology at the University of Cambridge (United Kingdom); Wilhelm Boland, Managing Director of the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology (Germany); Joanna Burger, Distinguished Professor of Biology at Rutgers University (United States); Gary K. Meffe, Consulting Editor of Conservation Biology and Adjunct Professor in the Department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation of the University of Florida (United States), and Daniel Simberloff, Gore Hunger Professor of Environmental Science at the University of Tennessee (United States).

This post is available in: English Español