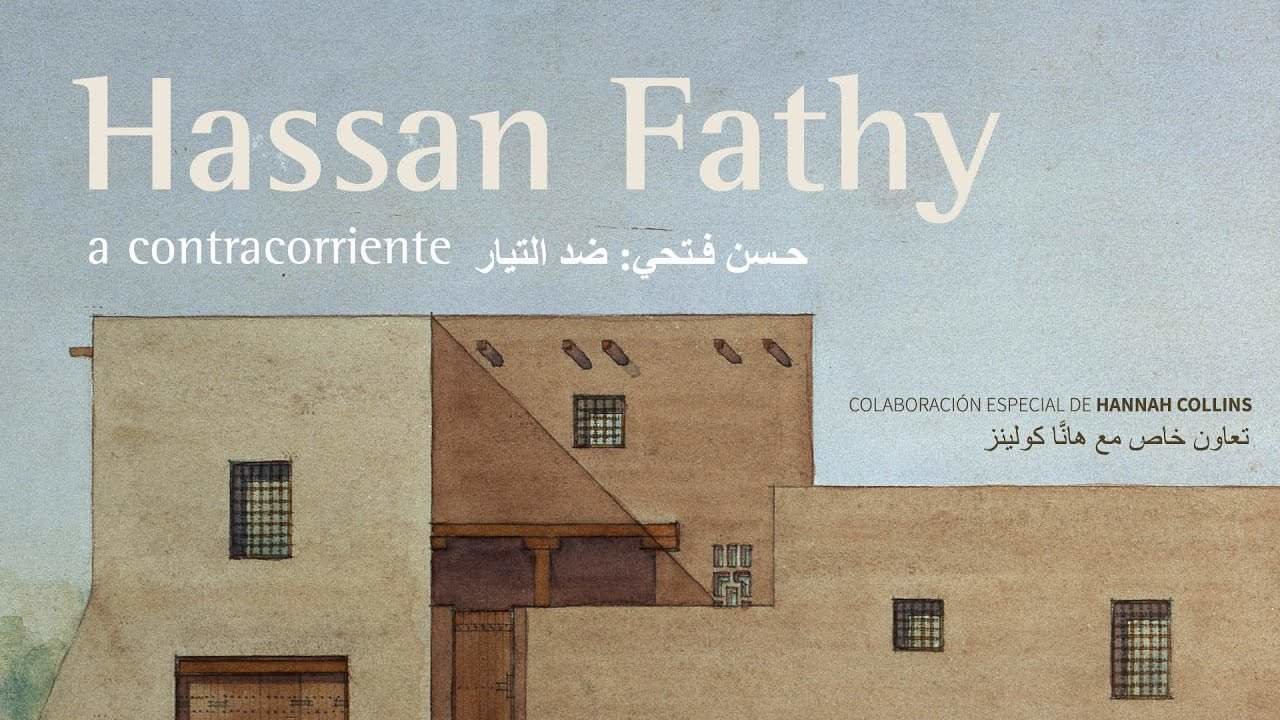

A pioneer in the revival of age-old building techniques, a century ago, he claimed the bioclimatic qualities of adobe houses and an ecological concept of urban planning tailored to the needs of human beings.

A century before global warming challenged the foundations of modern urbanism, an unknown Egyptian architect laid the foundations of some revolutionary concepts of sustainability and building ecology that few dispute today. In the first third of the 20th century, when Egypt managed to throw off the British colonial yoke and was steadily heading towards the future, a young architect named Hassan Fathy (Alexandria 1900 – Cairo 1989) surprised everyone by claiming adobe and clay as optimal building materials.

While the developed world was indulging in steel and concrete, Fathy advocated the age-old traditional architecture used by the fallahin (peasants) in the fiery lands of ancient Egypt. His proposals were greeted with utter bewilderment and seen as extravagance that went against the natural direction of history. Hassan Fathy was not deterred. And he persevered in his convictions. Soil dried in the sun and melted with straw was endowed with unbeatable thermal properties for an extremely hot ecosystem such as the Egyptian desert.

Fathy advocated the age-old traditional architecture used by the fallahin (peasants) in the fiery lands of ancient Egypt.

It was also a very cheap construction method within the reach of millions of people with limited resources. In fact, the Egyptian architect strove to make it possible for people without resources to build their own homes. His social commitment accompanied him throughout his prolific professional career. So much so that he was recognised as the ‘architect of the poor’, thanks in part to one of his works published under the title of the same name (“Architecture for the poor”, 1969).

In that book, which became internationally known, he explains one of the most innovative and suggestive projects of his professional biography. In 1946, he was commissioned by the government to plan a village to rehouse the gournis, the looters of the Pharaonic tombs. Hassan Fathy designed a complete programme of rural town planning. He studied in detail the customs of its future inhabitants in what was an exhaustive work of social anthropology to give birth to New Gourna, one of his most globally acclaimed architectural creatures.

In New Gourna he applied his innovative construction theories, learned in the Nubian region of southern Egypt in the early 1940s. From that trip he was fascinated by how the Nubians built barrel vaults without reinforcement and the way they made adobe bricks, wooden doors and ancient stained glass windows to protect the people from the desert. The new city was built on the outskirts of Luxor and could accommodate 7,000 people. The site included an open-air theatre, school, souk and mosque in addition to the dwellings. And, true to his construction principles, he used neither concrete nor steel.

‘Hassan Fathy was ahead of his time,’ says José Tono, a cultural manager and expert in his work, in a telephone conversation with EL CORREO DEL GOLFO: ‘He was one of the first to talk about sustainability, aeration and the use of traditional materials when no one else was doing so. In fact, his influence in the field of architecture is more intense today than ever, as his ideas have become more relevant in the third millennium. He collaborated with the Greek architect Konstantinos Doxiadis to rethink the cities of the future, more humane, better connected and less disturbed by the massive use of cars.

‘Hassan Fathy was ahead of his time,’ says José Tono, a cultural manager and expert in his work, in a telephone conversation with EL CORREO DEL GOLFO: ‘He was one of the first to talk about sustainability, aeration and the use of traditional materials when no one else was doing so. In fact, his influence in the field of architecture is more intense today than ever, as his ideas have become more relevant in the third millennium. He collaborated with the Greek architect Konstantinos Doxiadis to rethink the cities of the future, more humane, better connected and less disturbed by the massive use of cars.

‘The design of houses for the poor, which they could build themselves, was a truly revolutionary proposal that many architects have since maintained,’ says Tono, who in 2021 was the curator of an exhibition organised by Casa Árabe and the Egyptian Institute in homage to the African urban planner. In his opinion, Fathy was the most important Arab architect in contemporary history. In the 1940s and 1950s his work was not ‘sufficiently understood’ and it is today that ‘it is truly bearing fruit and is accepted by the whole world’.

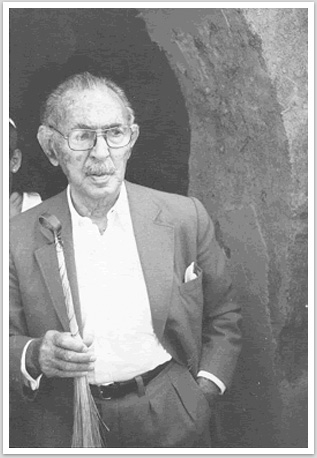

He graduated from Cairo University in 1926 and went on to hold various positions in the Egyptian government, as well as heading the Architecture Section of the Faculty of Fine Arts in the great Arab metropolis. He received the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 1980 and the Gold Medal of the International Union of Architects four years later.

Shahira Mehrez is an Egyptian designer and a personal friend of Hassan Fathy. In 2021, she was contacted by Casa Árabe to participate by videoconference in the tribute to the distinguished architect. ‘He wanted to build a better world for peasants and villagers by building on the traditions of the past,’ Mehrez said from Cairo. ‘He had a brilliant career as an architect, but he decided to go against the current, when he decided to go for architecture for the poor and in defence of ecology’.

He was a strong advocate of traditional neighbourhoods because, in his opinion, they breathed ‘humanity’.

The Egyptian designer admitted at the time that her work was not understood in her country. ‘Many people thought that Hassan Fathy wanted to take us back to the past when the people wanted to be modern’, she explained to José Tono, curator of the exhibition. But the Egyptian architect knew that ‘nobody is a prophet in his own country’, says Mehrez. ‘He was an idealist,’ he stresses. ‘An architect who wanted to save the habitat of Egyptian peasants and help them to live better’.

He travelled halfway around the world and worked in a handful of countries, from the United States to Spain. ‘And, of course, in many places in the Arab world,’ explains José Tono. He spent the last years of his life in a poor neighbourhood in Cairo. ‘His neighbours would ask him for money to pay for electricity and medicine,’ recalls designer Shahira Mehrez. He was a strong advocate of traditional neighbourhoods because, in his opinion, they breathed ‘humanity’. The same humanity that the Egyptian architect delivered throughout his biography to transform the lives of the fallahin and conceive more friendly urban spaces.

This post is available in: English Español