The idea of preserving heritage arose after the First World War, and steps have gradually been taken in this direction, with a number of international instruments being adopted for the protection of cultural and natural heritage. Some examples are:

- Recommendation defining the international principles applicable to archaeological excavations (1956).

- Recommendation concerning the Safeguarding of the Beauty and Character of Landscapes and Sites (1962).

- Recommendation concerning the Preservation of Cultural Property Endangered by Public or Private Works (1968).

The first international initiative for the protection of historic and natural monuments arose in 1959 in connection with the construction of the Aswan dam in Egypt, the aim being to protect the temples and archaeological excavations.

From then on, UNESCO and ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments and Sites) set to work on an international project to meet the widespread concern.

In 1965, a number of international organisations, including the IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature), took steps to create instruments for the protection of natural areas.

On 16 November 1972, the Convention for the protection of the World’s Cultural and Natural Heritage was approved in Paris. It stated:

Cultural heritage and the natural heritage are increasingly threatened with destruction not only by the traditional causes of decay, but also by changing social and economic conditions which aggravate the situation with even more formidable phenomena of damage or destruction.

It also states, amongst other things, that the study, knowledge and protection of cultural and natural heritage in different countries of the world promotes mutual understanding amongst nations.

In 1992, the World Heritage Convention decided to cover cultural landscapes. It granted them recognition and set up an international tool for protection, with a set of guidelines issued by the Committee for including cultural landscapes in the World Heritage List.

The Committee acknowledged that cultural landscapes represent “the joint works of man and nature” designated in Article 1 of the Convention:

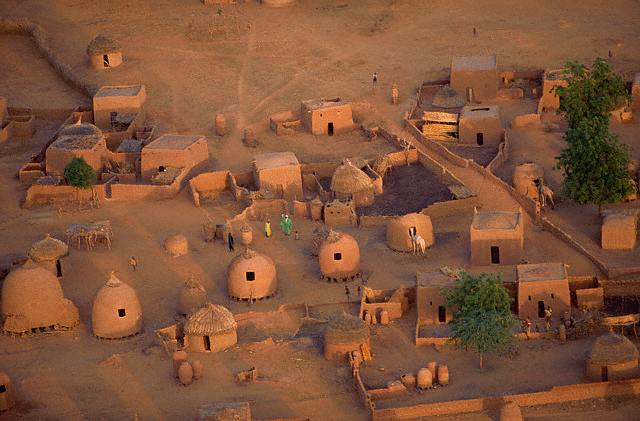

They are illustrative of the evolution of human society and settlement over time, under the influence of the physical constraints and/or opportunities presented by their natural environment and of successive social, economic and cultural forces, both external and internal.

Today, of the 66 cultural landscapes recognised by the World Heritage, only one is located within the Med-O-Med area of action:

Holy Valley (Uadi Qadisha) and the Cedars of God (Horsh Arz Al Rab). Lebanon.

Current situation of cultural landscapes in the Mediterranean.

Many meetings have been held over the years to lay down criteria. The latest Med-O-Med meeting held in France in 2007 brought together experts from nine countries in the Mediterranean basin as well as from UNESCO, ICOMOS, IUCN, the French government and regional and local authorities to discuss the Agro-Pastoral Cultural Landscapes of the Mediterranean. The purpose of this and of previous meetings, was to generate a set of guidelines for both the World Heritage Committee and its consultative bodies (ICOMOS and IUCN), and for Member States wishing to arrange inscription of a cultural landscape on the World Heritage List.

Many meetings have been held over the years to lay down criteria. The latest Med-O-Med meeting held in France in 2007 brought together experts from nine countries in the Mediterranean basin as well as from UNESCO, ICOMOS, IUCN, the French government and regional and local authorities to discuss the Agro-Pastoral Cultural Landscapes of the Mediterranean. The purpose of this and of previous meetings, was to generate a set of guidelines for both the World Heritage Committee and its consultative bodies (ICOMOS and IUCN), and for Member States wishing to arrange inscription of a cultural landscape on the World Heritage List.

In the document resulting from this meeting, the Mediterranean agro-pastoral cultural landscape was identified and described, the added values of such landscapes were mentioned, and recommendations were drawn up. Having defined the concept of pasture, the document described the characteristics of this type of landscape:

- “Mediterranean landscapes are considered to be those in a Mediterranean climate (dry to very dry summer, mild to cold winter)”.

- “The Mediterranean agro-pastoral societies have put in place tailored and complex systems, bringing together pastoralism, farming and forestry, intensive and extensive farming types (mostly mixed and to varying degrees in space and times), sedentary, nomadic and transhumant life ways”.

The document also covers tangible and intangible added values, including:

- “The Mediterranean agro-pastoral landscapes, existing in often spectacular settings so close to the mountains, possess highly valuable patterns in terms of heritage, such as the ecosystems and traces of the human activities that created them: paths, troughs, hand-built habitats, terraces, dry-stone walls, hydraulic works, etc”.

- “As for the other pastoral cultural landscapes in the world, these also hold associative or intangible values that cannot be dissociated from their tangible qualities. Mediterranean agro-pastoral societies possess knowledge, ‘know-how’, traditions and rituals of great cultural wealth”.

- “Their territories have often served as refuge to ethnic or religious minorities and often hold on their soils sacred sites of high symbolic value. All these values, tangible and intangible, are also characterised by a persistent tenacity from the past to nowadays”.

The document closes with a set of proposals and commitments for the near future to promote this line of action and, consequently, the promotion of such Mediterranean Agri-pastoral Cultural Landscapes.

Cultural landscapes classification

This post is available in: English Español