The period of Al-Andalus (8th-15th century) meant a great advance in the sciences of agronomy, irrigation systems and cuisine on the Iberian Peninsula. The introduction of many agronomic species from the East to Andalusia for culinary purposes during this period, but also for pharmacopoeia and the textile industry purposes, led to a great “Green revolution”, as some scholars have called it. Thus, species such as the artichoke, eggplant, lemon, bitter orange, melon and watermelon, basil and saffron, among many others, were introduced and acclimatized. In addition to this, the development of irrigation systems inherited from Rome and imported from the East, especially Persia, transformed not only the economy and cuisine of the Iberian Peninsula, but also its landscape, turning it into an orchard wherever water reached. Thus, the art of the table and good, healthy, and varied food spread to all strata of the population, while numerous treatises on agronomy, cooking and dietetics were written, some of them remaining reference books in Europe until the 17th century.

To gain an in-depth knowledge of a civilisation and the influences it has exerted on other cultures is not an easy task. Likewise, it is not easy to establish the limits that separate one civilisation from another over time, as culture cannot often be limited to one people or one period, but it is shaped by the fusion of a myriad of chronologically and geographically distinct elements.

In addition to this, a civilisation like the Islamic civilisation is like an immense “jigsaw puzzle”, in which, in order to understand its overall meaning, it is necessary to fit together piece by piece with infinite patience. One of these key pieces, essential for the understanding of any culture, refers to food, agriculture, and its landscape, with all the ludic, economic, and scientific connotations that these comprise.

Al-Andalus, the pearl of the West

Al-Andalus is the name given to the Islamic state founded by the Muslims on the Iberian Peninsula, which covered almost all of its territory. At the beginning of the 8th century, a contingent of Arabs and Berbers from the Maghreb arrived at the Peninsula, bringing with them a new religious, political and economic ideology, with marked Eastern influences. When fused with the existing Hispano-Gothic heritage, it resulted in a new and brilliant culture: the Andalusi culture. Their rule, which had a strong character that differed from the rest of the Islamic Empire, lasted until the end of the 15th century.

Thus, the art of the table and good, healthy, and varied food spread to all strata of the population, while numerous treatises on agronomy, cooking and dietetics were written, some of them remaining reference books in Europe until the 17th century.

The Islamic civilization not only penetrated the Iberian Peninsula, but also spread across the East and the north of Africa, specially the Maghreb, to the ends of the then known world… In this long journey, they were not only conquerors, but also transmitters of a new culture, which was itself the product of their own contribution and of all the positive elements they found and perfected as they moved towards the East.

This syncretism of cultural elements came about thanks to the scientific spirit and the legendary interest in learning that characterised the Muslims at the time, as we see reflected in the Qur’an and in numerous hadiths, or sayings, attributed to the Prophet Muhammad.

The “Green Revolution”

When the Muslims arrived at the Romano-Gothic Hispania, they found an unappealing food and landscape scenario. The land was dry and poor in resources, and the food was scarce and not very varied. It was based almost exclusively on the consumption of cereals and vines. The same thing was true for the rest of Europe, where fruit and vegetables were practically non-existent. Throughout the Middle Ages, Europe experienced periods of extreme scarcity and, as a consequence, certain basic foodstuffs were frequently lacking.

When fused with the existing Hispano-Gothic heritage, it resulted in a new and brilliant culture: the Andalusi culture. Their rule, which had a strong character that differed from the rest of the Islamic Empire, lasted until the end of the 15th century.

Faced with this shortage, the policy of the Umayyad dynasty, first rulers of Al-Andalus, was to promote agricultural development. To this end, first, a large number of ancient texts on agriculture were compiled and translated – most of them from the East. The existing irrigation systems inherited from the Romans in the Iberian Peninsula were perfected and increased, while technologies of Eastern origin were also imported and applied, both in water extraction and water conduction techniques.

Thus, new plant species were soon acclimatized and introduced from as far away as China, India and the Middle East, and large-scale cultivation of products already existing in Europe was encouraged.

Agricultural production experienced such a boost that it led to “food surpluses”. Its selling encouraged, at the same time, a specialization of trade, giving rise to a highly developed urban economy and culture.

What happened, in short, has been dubbed by many specialists a true “green revolution”.

The transformation of the landscape

Also led to a great transformation of the agricultural landscape of a large part of Iberian Peninsula in Medieval times. This transformation would later spread to the north of Africa, through the constant cultural exchanges between both regions brought about by the dynasties that ruled Al-Andalus and the current Morocco: the Almoravid (11th-12th centuries), Almohad (12th-13th centuries) and, later, the Nasrid and Marinid dynasties (13th-15th centuries). The hydraulic devices inherited from the Roman Empire or coming from the East, especially Syria and Iran, allowed water to reach the most remote corners, greening the land and populating it with orchards, farmhouses, and crops on a large scale.

This is the case of the large expanses of olive groves, as can be seen today in Jaén, Spain, and in Meknés, Morocco. Another example of landscape transformation was the creation of terraced cultivation, with beautiful dry stone walls that took advantage of the uneven terrain, such as those found in the Balearic Islands. The albuferas, from the Arabic al-buhayra, the lagoon, used for rice cultivation, proliferated in the Valencia region and the Aljarafe in Seville, providing large patches of greenery and humidity.

Ornamental and acclimatization gardens were equally numerous.

“All that part beyond Granada is very beautiful, full of farmhouses and gardens with their fountains and orchards and woods (…). Everything is beautiful and peaceful and so abundant with water that it cannot be more so, and full of fruit trees.” (Navagero, 1524)

Both in Spain and in the Maghreb, there are still beautiful Andalusian-style four-partite or transept gardens, generally with a central fountain and four sunken parterres, and irrigated by flooding through irrigation ditches, as a recreation of the Qur’anic gardens.

In the 10th century emerged an “Andalusian agronomic school”, which experienced a great development during the 11th-12th centuries. Many treatises on agriculture were written during this period, and agricultural trade habits were also registered in the hisba (treatises on habits and practices). The first botanical gardens were also created, notably in the taifas (kingdoms) of Seville, Toledo, and Almeria in the 11th century. These gardens frequently had a purely pharmacological and therapeutic purpose, and were created next to the hospitals themselves.

In addition, new methods of cultivation were researched and put into practice, such as the science of grafting, among others.

Agricultural policy

During the reign of Caliph Abderrahman III (929-961), Cordoba experienced one of the most prosperous periods of its existence, becoming a veritable centre of artistic, intellectual, and scientific activity, which allowed it to compete with cities of such brilliance as Baghdad, Damascus, Constantinople and even Fez.

The unifying and universalist policy of Caliph Abderrahman III, whose honorific name was al-Nasir Li-din Allah (he who fights victoriously for the religion of Allah), attracted many foreign ambassadors to Al-Andalus, prospering both at an economic and diplomatic level.

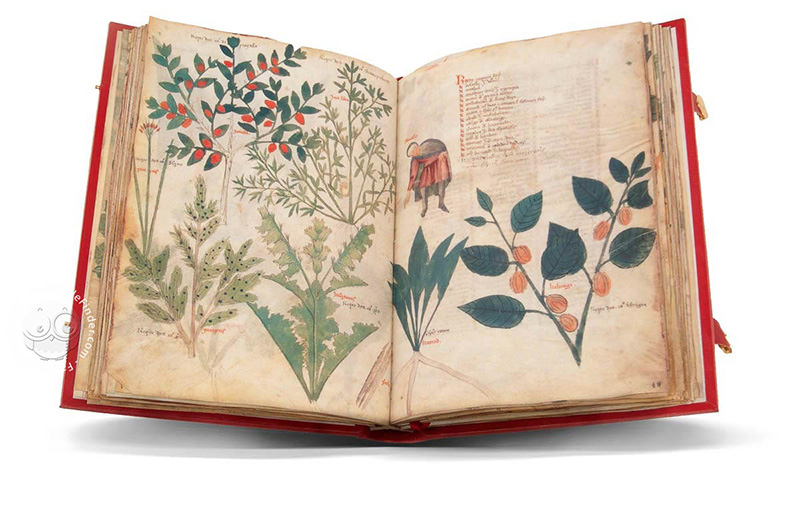

It would be one of these ambassadors, sent by the Emperor of Byzantium, who introduced a treatise that promote an extraordinary evolution in the field of science: the book of “Dioscorides”.

Along with this work, the Emperor sent a monk, Nicholas, to help in its translation, as the treatise was written in ancient Greek.

This book contained most of the known plants, along with their description, and a detailed list of their pharmacological and nutritional properties. This important treatise contributed greatly to increasing the knowledge of Al-Andalus’ scientists in the fields of agronomy and pharmacology.

The hydraulic devices inherited from the Roman Empire or coming from the East, especially Syria and Iran, allowed water to reach the most remote corners, greening the land and populating it with orchards, farmhouses, and crops on a large scale.

It was later, through the so-called School of translators of Toledo, founded by Castilian king Alfonso X in the 13th century, and the translators of Zaragoza, that most of this knowledge reached the rest of Europe, as numerous works were translated from Arabic into Latin.

The new waterworks

The description of Al-Andalus given by Arab (and later European) travellers and geographers whas that of a country with abundant dry land in the interior, mainly devoted to grazing and cereal cultivation. This contrasted with the wealth of its cities, mostly located on the banks of the most abundant rivers, surrounded by fertile plains where all kinds of fruit trees and vegetables were grown.

“There is so much beauty in the palaces, with the water pipes so artfully directed everywhere, that nothing more admirable is to be found. The running water is channelled through a very high hill and distributed throughout the fortress.” (Jerónimo Münzer, Viaje por España y Portugal, 15th century).

New water channels were created around these rivers: irrigation channels, ditches, weirs or dams whose function was to accumulate the water that would later be distributed, and qanats, which consisted of a system of wells connected to each other, which in Morocco are called Khetara and are preserved in some regions of the South, such as Figuig, leaving their lunar-like imprint on the skin of the most arid landscapes…

Numerous devices were also installed on the banks of rivers, such as na’ura (waterwheels), whose purpose was to facilitate the distribution of water. While waterwheels usually consisted of a hydraulic lifting wheel, other mechanisms included animal-driven waterwheels, consisting of a complex mechanism of wheels driven by animal traction.

These waterwheels are still preserved in various regions of Spain, although, logically, they have been greatly transformed over the centuries. Many of them are still in use, giving a special character to the riverbeds and the market gardens that surround them. This is the case of the so-called Albolafia, next to the Guadalquivir river in Córdoba (now disused), as well as the numerous norias in Valencia (Requena, La Ñora, etc.).

In Morocco, waterwheels were also common, as could still be seen in the region of Fez until a few years ago. However, the greatest transformation of the Moroccan agricultural landscape, as we know it today, is the ars, garsias and agdals (a word of Amazigh origin meaning cultivated fields), dedicated to the cultivation of citrus fruits and other fruit trees, as well as the palm groves in the south of the country.

In the orchards and gardens of al-Andalus, exotic ornamental flowers such as daffodils, wallflowers, roses and jasmine were intermingled with aromatic plants such as basil and lemon balm, and fruit trees of all kinds. In flowering season, these gave off an intense, sweet smell across the garden. The peacocks, unmoved and unperturbed, strutted around the pools.

These gardens were so beautiful that in the 11th century a new literary genre (rawdiyat and nawriyat, in Arabic) emerged in Valencia, describing with joy the gardens and fruits of the time. The poet Ali ben Ahmad recounts what he witnessed in the gardens of the al-Mansur al-munia in Valencia:

“Come and pour for me, while the garden wears a rain-draped alvexí of flowers, -already the sun’s cloak is golden and the earth pearls its green cloth of dew- in this pavilion like the sky to which the moon rises from the face of the one I love. Its stream is like the milky way, flanked by the diners, shining stars”.

The acclimatisation and introduction of new botanical species

Based on the achievements of the new agricultural techniques, the cultivation of new species such as the date palm and the banana soon took root in Al-Andalus, changing the cultivated landscape dramatically.

Other fruit species, such as the olive tree, already existed in the Iberian Peninsula, but it was the Hispano-Muslims who encouraged and organised their cultivation on a large scale. Ibn al-Awwam, who lived in Seville in the 12th century, attests to this in his Book of Agriculture, where he describes the beautiful olive groves of the Aljarafe, and the different qualities of the oil, valued for its gradations of sweetness, and highly regarded for its aromatic flavour and bromatological properties.

The result of these extensive olive tree plantations can be seen today in the fields of Andalusia (south of Spain), furrowed by hundreds of thousands of symmetrical green rows, as well as in the countries of the Maghreb, especially Morocco, which form the prototypical Mediterranean landscape.

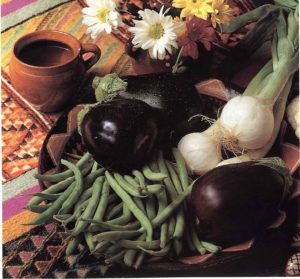

The Al-Andalus civilization introduced new products that are very popular today, not only in Spain but all across Europe, such as the aubergine (badinyana), which originated in India and spread across the Mediterranean via Persia. Among the most popular vegetables were the artichokes (al-jarsuf) and the asparagus, which had the property of preventing bad smells in the meat.

We also found pumpkin, cucumbers, green beans, garlic (which, like the onions, should not be eaten raw due to its bad smell), carrots, turnips, chard (as-silqa), spinach (isfanaj), leeks… This means that the Al-Andalus population could eat fresh vegetables all year round, which was a real first.

The fig, which became renowned in Al-Andalus to the point of being exported to the East, was introduced to the Peninsula from Constantinople in the time of Abderrahman II (822-852).

The most widely consumed fruits were the watermelon, which came from Persia and Yemen, the melon, original from Khorasan, and the pomegranate from Syria, which in the collective imagination became almost a symbol of Al-Andalus.

The fig, which became renowned in Al-Andalus to the point of being exported to the East, was introduced to the Peninsula from Constantinople in the time of Abderrahman II (822-852). Just as figs and grapes from Malaga were famous, so were bananas from Almuñécar.

Citrus fruits, such as lemon, grapefruit and bitter orange (naranya), were imported from East Asia. They were used to preserve foodstuffs, and their essences were also extracted to make perfumes. Oddly enough, orange trees, despite their great beauty, were considered to be a bad omen. Badis, the Zirid king of Granada (1002-1073), prohibited their planting and had the existing ones uprooted because, like many other Taifa kings, he blamed them for his military failures.

Citrus fruits, such as lemon, grapefruit and bitter orange (naranya), were imported from East Asia. They were used to preserve foodstuffs, and their essences were also extracted to make perfumes. Oddly enough, orange trees, despite their great beauty, were considered to be a bad omen. Badis, the Zirid king of Granada (1002-1073), prohibited their planting and had the existing ones uprooted because, like many other Taifa kings, he blamed them for his military failures.

Quince, apricot and countless other fruits were also acclimatised from other places.

Spices were widely used in the cuisine of Al-Andalus. Cinnamon was introduced from China, where it had been known for thousands of years, as well as saffron (za’faran), cumin (kammun), caraway, coriander, nutmeg, anise (anysun), etc. These spices, as well as being used as condiments in the preparation of dishes, were exported outside the Iberian Peninsula, also favouring the development of the economy.

Spices were widely used in the cuisine of Al-Andalus.

This variety of foods, especially vegetables, gave rise to a highly refined and complete cuisine from a dietary perspective. Manuscripts from Al-Andalus such as the Manuscrito anónimo de cocina del siglo XIII (“Anonymous 13th-century Manuscript on Cooking”), or the works on the qualities of food and its bromatological properties, produced, among others, by al-Arbuli, al-Tignari, Ibn Wafid, Ibn Bassal, etc., attest to this great wealth, and to the hedonistic and healthy approach to earthly life.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Andalusian “green revolution”, with the enormous introduction and acclimatisation of oriental and North African botanical species, transformed a large part of the landscape of the Iberian Peninsula and North Africa. Orchards, estates, farmhouses and gardens in al-Andalus, as well as ars, bustans, ryads and agdals in the Maghreb, dotted and greened the riverbanks and regions reached by water. This was also made possible by the implementation of earlier irrigation systems, especially Roman ones, as well as the introduction of eastern water distribution systems such as qanats and waterwheels. In addition, the Umayyad rulers’ agricultural and economic policies favoured this development, as did the large production of scientific, culinary and dietary treatises.

Inés Eléxpuru -FUNCI

References

Al Razi, Abu Bakr Muhammad b. Zakariya, Libro de la introducción al Arte de la Medicina o “Isagoge”, transl. Vázquez de Benito, M. C., Salamanca, 1979.

Arié, R., España Musulmana, Barcelona, 1987.

Chalmeta, P. El señor del zoco en España, Madrid, 1973.

De la Granja, F. “La cocina arabigoandaluza según un manuscrito inédito: Fadalat al-Jiwan”, extract of thesis, Madrid, 1960.

Eguaras, J. Ibn Luyun: Tratado de Agricultura, Granada, 1975.

Eléxpuru, I. y Serrano, M., Al-Andalus, magia y seducción culnarias, Madrid, 1991.

Eléxpuru, I. La cocina de al-Andalus, Madrid, 1994.

Glick, T., Islamic and Christian Spain in the Middle Ages, Princeton, 1979.

Huici Miranda, A., Traducción española de un manuscrito anónimo de siglo XIII sobre la cocina hispano-magribí, Madrid, 1966.

Ibn al-Awam, Libro de la Agricultura, trad. Banqueri, Madrid, 1802, facsimile edition, Madrid, 1988, I-II.

Ibn Bassal, Libro de la Agricultura, trad. J. M. Millás Vallicrosa, M. Aziman, Tetuan, 1955.

Ibn Wafid, El libro de la almohada, Álvarez de Morales, C., Toledo, 1981.

This post is available in: English Español